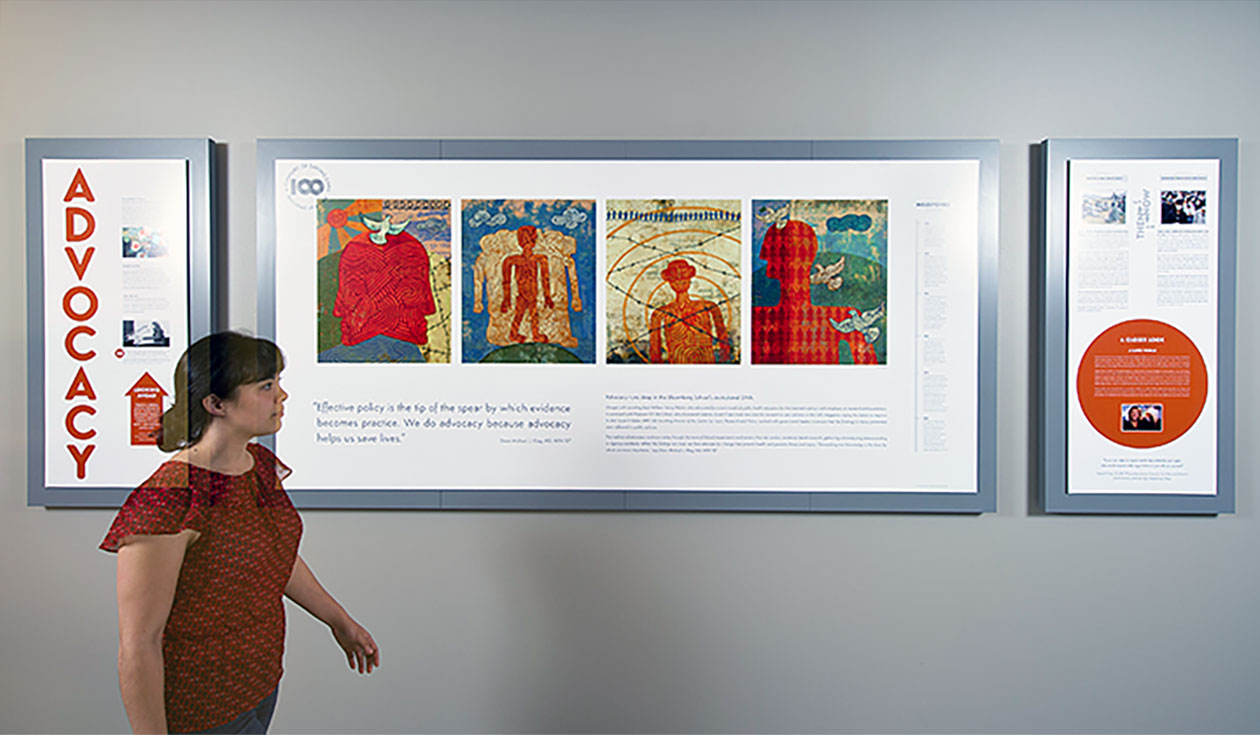

Advocacy

“Effective policy is the tip of the spear by which evidence becomes practice. We do advocacy because advocacy helps us save lives.”

JHSPH Dean Michael J. Klag, MD, MPH ’87

Advocacy runs deep in the Bloomberg School’s institutional DNA.

It began with founding dean William Henry Welch, who advocated for a new model of public health education for the twentieth century with emphasis on research and academics. It continued with Professor E.V. McCollum, who discovered vitamins A and D and took time from his research to pen columns in McCall’s magazine urging the nation to improve its diet. Susan P. Baker, MPH ’68, founding director of the Center for Injury Research and Policy, worked with government leaders to ensure that her findings in injury prevention were reflected in public policies.

The tradition of advocacy continues today through the work of School departments and centers. First we conduct evidence-based research, gathering and analyzing data according to rigorous standards. When the findings are clear, we then advocate for change that protects health and prevents illness and injury. “Generating new knowledge is the lever by which we move mountains,” says Dean Michael J. Klag, MD, MPH ’87.

Timeline

1953

1953

Influenced by a committee co-chaired by Dean Ernest L. Stebbins, MD, MPH ’32, Congress approves the creation of a new cabinet- level Department of Health, Education and Welfare.

1958

1958

Dean Stebbins, as president of the Association of Schools of Public Health, successfully persuades Congress to pass the Hill-Rhodes Public Health Professional Training Act, which provided scholarships to 60 percent of all U.S. public health graduates during the program’s 20 years.

1961

1961

Kerr L. White, founding chair of Health, Policy and Management, and colleagues Barbara Starfield, MD, MPH ’63, Vicente Navarro, MD, PhD, DrPH ’69, and Sam Shapiro, first director of Health Services Research, spearhead the effort to establish primary care as a major focus of national health policy.

1967

1967

In response to testimony by public health advocates, including Phyllis Piotrow, PhD ’71, Congress amends Social Security to mandate federal support for family planning and earmarks $35 million in USAID’s budget for this purpose.

1983

1983

Drawing from John Kantner and Melvin Zelnik’s pioneering surveys of adolescent female sexuality, Laurie Schwab Zabin, PhD ‘79, demonstrates that the highest proportion of adolescent pregnancies occur in the first months after girls become sexually active and that school-based family planning clinics reduce rates of teen pregnancy by 15 percent.

2013

2013

The School convenes more than 20 global experts at the Summit on Reducing Gun Violence in America to summarize relevant research and its implications for policymakers and concerned citizens, identifying several research-based policies that address the problem in the U.S.

Then & Now

Then: Creating Global Health Equity

CARL E. TAYLOR, FOUNDING CHAIR OF INTERNATIONAL HEALTH, spent his career improving the lives of the world’s marginalized people. Taylor did pivotal research that defined the synergism between nutrition and infection as well as malnutrition and child mortality. He was also instrumental in recognizing the community health benefits of women’s empowerment.

A World Health Organization advisor from 1957 through 1983, Taylor served as its leading consultant for the 1978 Alma-Ata World Conference on Primary Health Care in Kazakhstan. The WHO/UNICEF Alma-Ata Declaration was the first international statement to underscore the importance of primary health care by addressing the preventive health needs of populations, particularly in developing nations. A touchstone of the global health equity movement, the Declaration asserted that health is a human right and reaffirmed that community-based primary health care is the most efficient, cost-effective way to organize a health system and produce better outcomes. The statement also urged international cooperation to better utilize world resources.

When the Alma-Ata Declaration’s aim of “Health for All by 2000” was criticized as too broad, a conference the following year focused on specific targets, including oral rehydration treatment, breast- feeding, immunization, female literacy and family planning. Taylor continued to push the global agenda for primary health care throughout his long life, working in more than 70 countries to build more equitable societies.

Now: Advancing Human Rights and Health

WHEN CHINA SUPPRESSED INFORMATION ABOUT SARS IN 2003, the disease spread quickly. “People saw dramatic evidence that ... limitations on information let that epidemic get out of control,” says Chris Beyrer, MD, MPH ’90. As director of the Center for Public Health and Human Rights, Beyrer can list violations of fundamental human rights that endanger public health on every continent.

His Center uses population-based tools to quantify the health effects of human rights abuses. Epidemiologists assess the impact of discrimination and political conflict against marginalized groups, the violation of privacy rights, mass rape as a weapon of war, torture and ethnic cleansing. And their findings can drive policy changes.

Advocates for human rights and health abound at the School. Leonard Rubenstein, senior scientist at the Center, works to help protect health workers and facilities, especially in conflict zones. Rubenstein also prepares class action suits to improve medical and mental health services for prisoners. Robert Lawrence, co-founder of Physicians for Human Rights, investigates international rights violations, with an increasing focus on refugee health and human rights. Joanne Rosen, director of the Clinic for Public Health Law and Policy, explores how laws that impact intimacy affect health, especially in the LGBT community.

A CLOSER LOOK

A Safer World

Unintentional injuries are the biggest threat to the health of children in the U.S.—but injuries were not always considered a public health problem. That changed when Susan P. Baker, MPH ’68, became founding director of the Center for Injury Research and Policy. She studied aviation fatalities, occupational injuries and traffic deaths, prompting laws mandating child restraints in automobiles. She also developed the Injury Severity Score, now the standard for predicting injury mortality.

Stephen Teret, JD, MPH ‘79, who followed Baker as Center director, championed effective warning labels on toys with choking hazards. His successor, Ellen MacKenzie, PhD ’79, MSc ’75, found that traumatic injury survivors required more than physical healing to achieve positive outcomes and helped design programs to improve their lives. Current Center director Andrea Gielen, ScD ’89, ScM ’79, helped identify barriers to child protection faced by low-income parents and launched the CARES Mobile Safety Center, a house on wheels that educates parents about home safety and provides low-cost safety products.

Center faculty were among the first to view rearm deaths as a public health problem and study safer gun designs and regulations. And researchers have explored strategies to reduce the number of motor vehicle crash injuries, demonstrating, for example, that graduated driver licensing programs for teens reduce the risk of crash fatalities by more than 35 percent.

Display Credits

Main Illustration

- Ferruccio Sardella

Other Content

- Can You Hear Me Now? Illustration: Dung Hoang, Hopkins Bloomberg Public Health magazine

- Karen Davis Photo: The Alan Mason Chesney Medical Archives

Then and Now

- Then: Creating Global Health Equity/Carl Taylor Photo: Hopkins Bloomberg Public Health magazine, Fall 2011

- Now: China SARS Photo: Peter Treanor/Alamy Stock Photo

A Closer Look

-

Andrea Gielen: Chris Hartlove