Introduction

The introduction to the resource guide provides background on the HPRIL project, the need for innovative tools to address participant retention, and the importance of evaluating WIC innovations. It provides an overview of the five local WIC agency projects funded through HPRIL and describes HPRIL’s goal of building local agency capacity to implement and evaluate innovation projects beyond the five HPRIL subgrantees. The introduction concludes with a description of the resource guide and its components.

Introduction Contents

Background

Established in 1974, the Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants and Children (WIC) is administered by the Food and Nutrition Service (FNS) of the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA). WIC provides nutritious foods, nutrition education, breastfeeding promotion and support, and referrals to health and social services to participants at no charge to participants. WIC serves low-income pregnant, postpartum and breastfeeding women, infants, and children up to age 5 who are at nutritional risk.1 Although WIC is funded through grants from the federal government, it is administered by 89 state agencies through approximately 1,900 local agencies and 10,000 clinics.

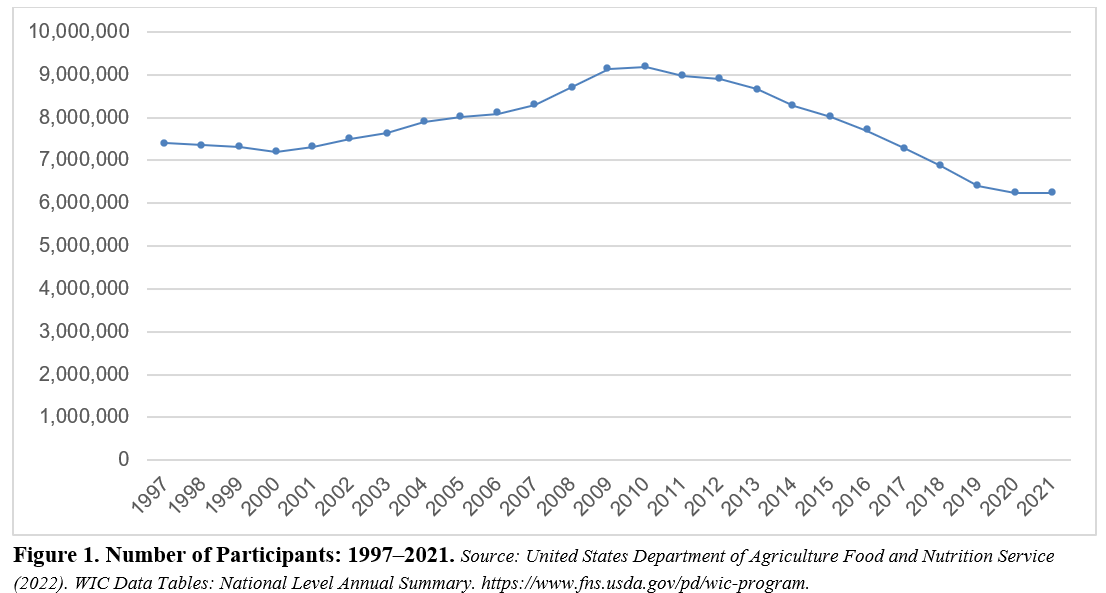

WIC is a discretionary program and is funded through the federal appropriations process each year. Funding for WIC is dependent on many factors, including current and projected WIC participation rates. After WIC received full funding in 1997, participation rates increased (from 7.4 million low-income women, infants, and children in 1997 to 9.2 million in 2010).2 As the economy improved following the recession of 2008-2009, the number has fallen consistently each year (to 6.2 million in 2021) (see Figure 1).

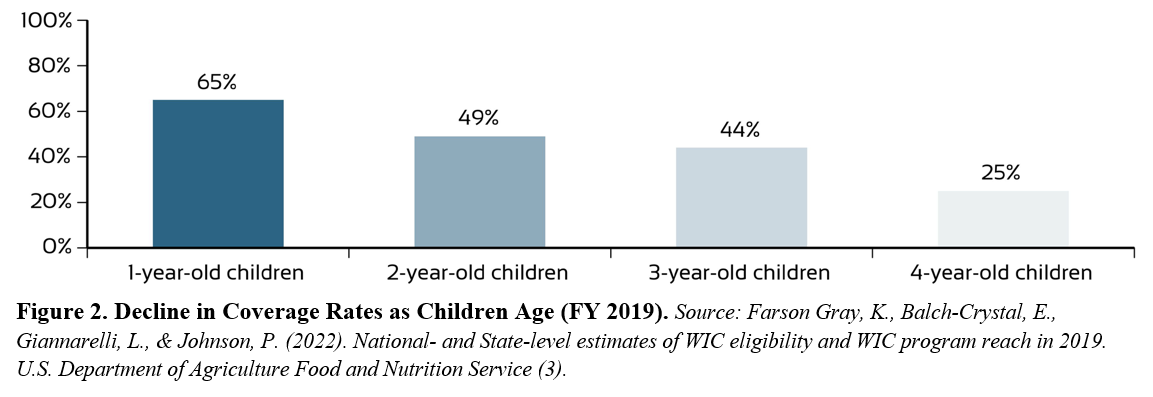

In addition to participation rates, it is important to consider WIC coverage rates (i.e., the percent of eligible people in the population who participate in WIC). The coverage rate in 2019 for all participants was 57.4%, with the highest among WIC-eligible infants (98%).3 The coverage rate for children was 44.8%, and for pregnant women was 52.3%.3 Research demonstrates that the sharp decline in participation after infancy is unlikely to reflect a trend of upward economic mobility of the family.4

While WIC participation generally reflects broader economic, social, and demographic trends, there are many additional factors that have contributed to declines in WIC participation over the last decade. According to a growing body of research, common themes for non-participation include lack of knowledge of the program and of eligibility requirements, social stigma, lack of transportation, language barriers, fears around threats to immigration status, and lack of childcare.5 6 7 8 Issues with the quality of service delivery include problems with appointment scheduling, documentation burdens, low frequency of communication from WIC office, inconsistent information provided by WIC and other care providers, and long wait times.8 9 According to Whaley et al (2017), factors associated with children remaining in WIC included being breastfed, prenatal intention to breastfeed, receipt of online education, months of prenatal enrollment in WIC, other family members receiving WIC, and participation in Medicaid.6 Factors associated with children dropping out of WIC included missing benefits in the months leading up to first birthday, under-redemption of WIC benefits, and English language preference.

Photo source: https://wicbreastfeeding.fns.usda.gov/learn

Within the last several years, WIC has made changes to best meet the needs of WIC participants and to stay nutritionally, culturally, and technologically relevant. To address clinic service issues, agencies have implemented messaging platforms for appointment reminders, education and breastfeeding support, 9 10 11 as well as mobile phone applications for assistance in shopping, appointment reminders, keeping track of WIC foods, and nutrition education.12 13

The development and application of new tools (digital and otherwise) is core to quality provision of WIC services and likely to address barriers to retention. While there have been many tools developed and implemented over the last decade, few have been studied for impact on retention. The Hopkins Participant Research Innovation Laboratory for Enhancing WIC Services (HPRIL) sought to fill this research gap by supporting WIC agencies to design innovative tools aimed at retaining at-risk populations and evaluating the impact of the innovative tools on child retention. A team of researchers at the Johns Hopkins University Bloomberg School of Public Health entered into a multi-year cooperative agreement with the USDA to launch HPRIL. Starting in 2019, HPRIL funded and supported five local WIC agency projects lasting 18 months, providing technical assistance and building local agency capacity throughout the project. Please see the next section, HPRIL Local Agency Subgrantee Project Overview, for more details.

References

1 United States Department of Agriculture Food and Nutrition Service (2013). WIC at a Glance. https://www.fns.usda.gov/wic/about-wic-glance.

2 United States Department of Agriculture Food and Nutrition Service (2022). WIC Data Tables: National Level Annual Summary. https://www.fns.usda.gov/pd/wic-program.

3Farson Gray, K., Balch-Crystal, E., Giannarelli, L., & Johnson, P. (2022). National- and State-level estimates of WIC eligibility and WIC program reach in 2019. U.S. Department of Agriculture Food and Nutrition Service. https://www.fns.usda.gov/wic/national-state-level-estimates-eligibility-program-reach-2019.

4 Pati, S., Siewert, E., Wong, A.T. et al. The Influence of Maternal Health Literacy and Child’s Age on Participation in Social Welfare Programs. Maternal and Child Health Journal 18, 1176–1189 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10995-013-1348-0

5 Liu, C.H., & Liu, H. (2016). Concerns and structural barriers associated with WIC participation among WIC-eligible women. Public Health Nursing, 33(5), 395-402. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5527844/.

6 Whaley, S., Whaley, M., Au, L., Gurzo, K., & Ritchie, L. (2017). Breastfeeding Is Associated with Higher Retention in WIC After Age 1. Journal Nutrition Education and Behavior, 49, 810-816. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/28890264/.

7 National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine (NASEM). (2017). Review of WIC Food Packages: Improving Balance and Choice: Final Report. NASEM; Health and Medicine Division; Food and Nutrition Board; Committee to Review WIC Food Packages. Washington, DC: National Academies Press. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/28605175/.

8 United States Department of Agriculture Food and Nutrition Service (2021). Third National Survey of WIC Participants. Brief Report 4: Retention and Potential Barriers to Participation Among WIC Participants. https://www.fns.usda.gov/wic/third-national-survey-wic-participants.

9 The Food Research and Action Center (2019). Making WIC Work Better: Strategies to Reach More Women and Children and Strengthen Benefits Use. https://frac.org/wp-content/uploads/Making-WIC-Work-Better-Full-Report.pdf.

10 Colorado WIC Program. (2015). Texting for Retention Program. Final Report: WIC Special Project Grant, Fiscal Year 2014. Denver, CO: Colorado Department of Public Health and Environment. https://wicworks.fns.usda.gov/sites/default/files/media/document/Colorado%20TFRP%20Final%20Report.508.pdf.

11 Vermont State WIC Program (2017). WIC2FIVE: Using Mobile Health Education Messaging to Support Program Retention. Vermont 2014 WIC Special Project Mini-Grant. Final Report. Burlington, VT: Vermont Department of Health WIC Program. https://wicworks.fns.usda.gov/sites/default/files/media/document/VT.Final_report_508.pdf.

12 Brusk, J.J. & Bensley, R.J. (2016). A Comparison of Mobile and Fixed Device Access on User Engagement Associated With Women, Infants, and Children (WIC) Online Nutrition Education. JMIR Research Protocols, 5, e216. https://www.researchprotocols.org/2016/4/e216/.

13 Hull, P., Emerson, J., Quirk, M., Canedo, J., Jones J., Vylegzhanina, V., Schmidt, D., Mulvaney S., Beech, B., Briley, C., Harris C., & Husaini. B. (2017). A Smartphone App for Families With Preschool-Aged Children in a Public Nutrition Program: Prototype Development and Beta-Testing. JMIR Mhealth Uhealth. 5, e102. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5559651/.

HPRIL Local Agency Subgrantee Project Overview

Pima County Health Department (PCHD) introduced WICBuzz, a drip marketing text message campaign. The campaign featured targeted nutrition education and WIC brand awareness messages aimed at parents and guardians of children from birth to age four who are currently enrolled in PCHD WIC as well as ad hoc messages to remind or educate caregivers of when recertification is due and how the recertification process works. WICBuzz messaging was tailored based on the participants’ primary language (English or Spanish) and child’s age. Participants had the option to opt out of receiving messages. To read Pima County’s final report, please click here.

Yavapai County WIC, AZ-WIC-in-a-CLICK

Yavapai County Health Department WIC introduced WIC-in-a-CLICK, an online platform allowing clients to receive nutrition education through electronic devices including cell phones, tablets or computers. Online sessions were provided one-on-one as well as in a group setting. WIC-in-a-CLICK was available to all participant categories with a focus on reaching families who have children ages 1 through 4. While the development of online nutrition education was not a new concept, WIC-in-a-CLICK was unique in that it offered an on-demand option. On-demand classes consisted of clients requesting an appointment and within 1 hour receiving an invite to a Zoom session. Once the session was completed, food benefits were loaded onto the family’s eWIC (i.e., EBT) card. To read Yavapai County’s final report, please click here.

The Florida Department of Health Miami-Dade WIC Program implemented an integrated media marketing strategy that digitally targeted participants and potential participants with display ads, posts and videos using precise geographical location (geo-location) technology and customized messaging for their target population. The target audience for this intervention included mothers and family members currently receiving WIC benefits and potentially eligible mothers/family members of children aged 1-3 years of age. Messages were culturally and socially relevant to current barriers to participation. In addition, the tool provided brand awareness, specifically to promote WIC services, eligibility and benefits after infancy. Social media posts, YouTube videos, and other advertisements were continually updated and strategically deployed based on what performed well according to Google analytics.

Cabarrus Health Alliance, NC-QLess Online Scheduling

Cabarrus Health Alliance (CHA) implemented an Online Appointment Scheduling (OAS) called QLess. It was available by smartphone and/or computer and allowed participants to make appointments and sent text reminders. This tool assisted with appointment wait times by facilitating easy, immediate, and reliable access to WIC services. To read the Cabarrus Health Alliance’s final report, please click here.

Public Health Solution, NY: What Matters to You and Digital Care Coordination

Public Health Solutions (PHS) implemented a participant-centered conversation known as “What Matters to You?” (WMTY) and partnered with UniteUs, a technology-enabled coordinated accountable network focused on the social determinants of health. The WMTY approach targeted families at greatest risk of dropping out of WIC—those with children approaching their 1st and 2nd birthdays. WMTY involved asking these families open-ended questions to identify highest priority needs and connecting those families with resources in the community to address those identified needs. This approach took the onus off the participant to follow up on their referral.

Building Capacity Beyond the Five Funded Agencies

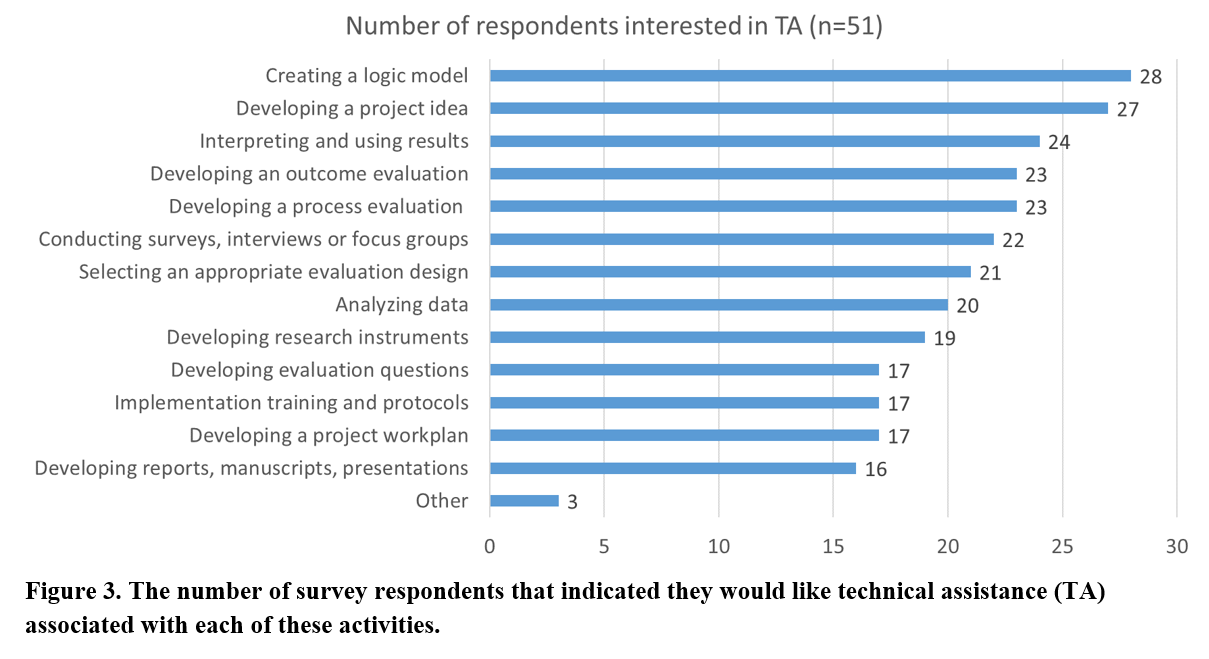

In addition to training and supporting the five local agencies funded through the project, HPRIL was also tasked with building the capacity of additional local agencies to implement and evaluate retention-related projects. In order to best target our capacity-building materials, the HPRIL team conducted a survey in November 2020 which assessed the needs of local WIC agencies in the development, implementation, and evaluation of innovation projects. There were a total of 78 responses to the survey (73 of which were from local agency staff members), and the results indicated that 64% of respondents had implemented projects in the past five years to improve participant retention. 65% of respondents stated that they would be interested in receiving more resources and training regarding program planning, implementation and evaluation.

The results supported our previous insight that despite the adoption of a growing number of strategies aimed at addressing participant retention at the local level, there remains a gap in consistent evaluation and dissemination of findings, which leaves WIC agencies to wonder which strategies are effective. These results are further supported by the most recent National WIC Association Research Needs Assessment, which states that “evaluation of current technological innovations in WIC is needed,” as is research that explores which responses to WIC caseload declines have been most effective in targeting vulnerable populations.1 USDA/FNS has also signaled support for greater modernization and technology efforts in WIC and the need to evaluate new tools. In 2021, Congress provided USDA/FNS with $390 million to carry out outreach, innovation, and program modernization efforts to increase participation and redemption of benefits in WIC and the WIC Farmers’ Market Nutrition Program (WIC FMNP).2

In terms of guidance, the findings from the needs assessment indicate that areas of particular interest include creating a logic model, developing a project idea, interpreting and using results (and data more broadly), and developing process and outcome evaluations. These results, in combination with HPRIL’s experience working with the five funded agencies over the course of three years, indicate that a resource guide providing instruction and tools for implementing and evaluating innovative projects would be useful to WIC agencies.

References

- National WIC Association (2018). NWA Research Needs Assessment. https://www.nwica.org/RNA.

- United States Department of Agriculture Food and Nutrition Service (2021). WIC and WIC FMNP - American Rescue Plan Act - Program Modernization. EO Guidance Document # FNS-GD-2021-0023. https://www.fns.usda.gov/wic/american-rescue-plan-act-program-modernization.

Resource Guide Description

Implementing and Evaluating Innovation Projects: A Resource Guide for Local WIC Agencies is designed to be used by state and local agencies (with an emphasis on local agencies) to develop, implement, and evaluate your own innovative project. Resources in the guide include templates, guidance documents, training materials, data collection tools and videos used throughout the HPRIL project and were developed by HPRIL and the five subgrantee agencies.

The guide is divided into four sections:

Project Development Implementation Evaluation Dissemination

The organization of the resource guide is meant to serve as a step-by-step process for agencies to use when considering launching a new innovative tool aimed at retaining WIC participants. However, if you are further along in the process of implementing a new tool, you are encouraged to skip to whichever section you feel you could use assistance with. In fact, there is an additional section Direct Links to Tools and Templates that provides direct links to all of the tools and templates in the resource guide, for quicker access.