Background

The WIC Program

The United States Department of Agriculture (USDA) Food and Nutrition Service (FNS,) through the Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women Infants and Children (WIC), is responsible for providing federal grants to states, Indian reservations and U.S. territories for supplemental foods, nutrition education as well as health care and social service referrals for low income pregnant, breast-feeding and postpartum women and infants and children up to age five who are found to be at nutritional risk. Almost one half of all newborns in the U.S. participate in the program. Approximately 7 million WIC participants currently receive an age specific monthly food package that include fresh fruits and vegetables to supplement the diets of pregnant and postpartum women as well as children’s diets during critical periods of growth and development. The WIC program has been extensively evaluated and considered to be one of the nation’s most effective and successful nutrition programs.

Participating in WIC Improves Child Outcomes

The WIC program is heralded as a public health success story. Since its inception over forty years ago, research has shown that WIC not only improves the lives of participating families but is cost-effective. WIC has also been found to be cost effective, saving up to $3.50 in future healthcare costs for every dollar spent on the Program (Oliveira & Frazao, 2009). The USDA estimates that every dollar spent on pregnant WIC participants saves Medicaid--an entitlement program that provides free health insurance to low-income individuals-- $1.77 to $3.13 for health care costs occurring in the first two months after delivery (Gordon & Nelson, 1995; U.S. General Accounting Office, 1992). The savings can be attributed to longer periods of gestation by the mother and a reduced risk of her delivering an infant born at a low birth weight, prematurely or require non-routine care in the Neonatal Intensive Care Unit, and is estimated by comparing pregnancy outcomes of mothers that participated in WIC prenatally with those eligible but did not participate (Sonchak, 2016).

WIC has a strong record of preventing children’s health problems and improving their long-term health, growth and development. Childhood WIC participation is associated with numerous positive health and cognitive outcomes when compared to children eligible but not participating in WIC. Children receiving WIC benefits are more likely to receive regular preventative health care, such as well-child check-ups, immunizations and routine dental care (Hunter, et.al., 2016; Buescher, et. al., 2003). They consume more nutrient dense foods including fruits, vegetables, and whole-grains that contribute to an overall better quality diet (Schultz, Shanks & Houghtaling, 2015). Children participating in WIC fare better academically; cognitive benefits of WIC participation include higher vocabulary and reading scores and increased ability for numerical recall (Jackson, 2015).

As Eligible WIC Children Grow Older, Fewer Participate in the Program

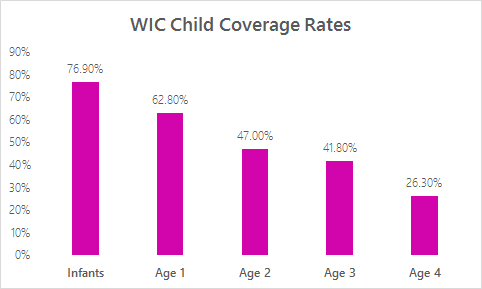

Despite the need for the program, and demonstrated effectiveness, there are recognized problems of retention/continued participation, particularly for children 1-4 years. Over half of all the infants in the United States participate in the WIC Program, but only over a quarter of all children between the ages of 1-4 years continue to receive WIC benefits (Oliveira and Frazao, 2015). The USDA’s Food and Nutrition Services estimates that 76.9 percent of infants eligible for WIC participate; but less than half of eligible children participate (Trippe et al, 2018). The sharp decline in participation after infancy is unlikely to reflect a trend of upward economic mobility of the family (Pati et. al., 2014). Among children eligible for WIC, age has been found to be a significant predictor of WIC participation independent of race/ethnicity, household size, maternal education, marital status, employment and age (Pati, et. al 2014). One study found a 34% decrease in WIC participation of families with eligible children between the ages of 1 and 2; and for each one-month increase in the age of the child past 12 months, the odds of participating in WIC decreased by 4% (Pati, et. al 2014).

There are Many Barriers for Families to Remain Enrolled in WIC Beyond Their Child’s First Birthday

Research has explored and identified barriers to continued participation in WIC, and the topic was recently the focus of a review by the National Academy of Science, Engineering and Medicine (NASEM, 2017). Across studies, common reasons cited for non-participation include lack of knowledge of the program, of eligibility, general problems faced by participants in terms of lack of transportation, language barriers, immigration problems, and lack of child care. Issues with the quality of service delivery are also barriers, and include problems with core client services (scheduling, timing, wait times/time burden, not liking WIC foods), and with vendor services (hard to find WIC foods, vendor hours, problems with purchasing and interactions with vendors). A 2014 survey of WIC agencies focusing specifically on child retention identified lack of knowledge of eligibility, frequency of certification, less child friendly clinic environments, less interaction with pediatric care providers (enabling linkage), conflicts with child food preferences, and competing priorities in terms of work and other activities (shopping, childcare, other) as additional barriers to participation.

Analyses of WIC participant patterns and behaviors can aid in understanding the nature of the problem and perhaps identify eligible participants at risk for leaving the program. Whaley et al (2017) used the WIC administrative database to identify factors associated with infant recertification at age 14 months. Infants, breastfed from 6 to 12 months, were more likely to be recertified in WIC by 14 months of age than infants who were fully formula fed, with increasing intensity of breastfeeding having increasing odds of recertification. Other factors positively associated with recertification by 14 months were prenatal intention to breastfeed, receipt of online education, months of prenatal enrollment in WIC, other family members receiving WIC, and participation in Medicaid. Factors negatively associated with recertification by 14 months included missing benefits in the months leading up to first birthday, under-redemption (<75%) of WIC benefits, and English language preference.

There is Promising Work Addressing Child Retention in WIC

Overall, state and local agencies have been working to improve participant retention, including children 1-4 years. To address clinic service issues, agencies have implemented messaging platforms for appointment reminders, education and breastfeeding support (Colorado WIC Program, 2015; Vermont State WIC Program, 2017; Whaley et al., 2017); mobile phone applications for assistance in shopping, appointment reminders, keeping track of WIC foods, and nutrition education (Brusk & Bensley, 2016; Hull et al., 2017). Indeed, many clinics already provide appointment reminders and other basic communications to participants via text message and this has largely been well-received by both staff and participants. Texting provides an opportunity to expand communications as well as answer follow-up questions, and schedule appointments between clinic staff and WIC participants via two-way text messaging, which has been piloted by the Oregon State WIC Program (Neuberger, 2016).

Colorado WIC Program (2015) piloted a quasi-experimental study to evaluate the impact of texting on participation and recertification. Clinics were assigned to one of three separate groups: control, which did not implement the texting program; basic innovation, which implemented appointment reminders by text; and augmented innovation, which implemented additional information about WIC benefits by text, in addition to appointment reminders. Scheduling practices (standard (three months in advance) versus same/day scheduling (same day or next day when the previous 3 months benefits have expired)) were also examined. Augmented innovation text messaging was found to have the greatest impact on retention on multiple measures including enrollment, recertification and reinstatement in pilot WIC clinics, especially those with standard scheduling. Same/next day scheduling clinics with augmented text messaging also saw improvement in retention but not statistically significant. Basic innovation texting did not see any improvement in retention.

To address transportation and competing time barriers, agencies have moved WIC into non-traditional spaces (shopping malls, homeless shelters), created mobile WIC clinics to reach rural areas (Virginia WIC Program, 2017; Rodriguez, 2018), and created partnerships with other services which support child development, such as Head Start and daycare/pre-school programs, organizations which support families (e.g., religious organizations), and others, including state and federal programs (e.g., Medicaid). Outcome evaluations for some of these strategies are pending.

To address perceptions and misperceptions about the focus of the WIC program other than pregnancy and infancy; marketing and outreach initiatives have been developed. The Illinois “WIC to 5” strategy (Illinois AAP, 2015), is a good example of this type of approach. It emphasized 5 key messages “Save, Nourish, Grow, Connect and Learn”, to emphasize that WIC strives to help clients address their needs from the woman’s pregnancy through the child’s pre-school years. Outcome evaluation of this program is pending.

Seventy-seven percent of WIC participants own smartphones and use them to find health information (Pew Research Center, 2016). Research has confirmed that online education and mobile applications are acceptable and accessible to WIC participants (Hull et al., 2017; Au et. al., 2016; Bensley et. al., 2014). In response to this, states have developed both online and mobile tools to provide participants additional options for managing their WIC experience, particularly in the areas of nutrition education and grocery shopping, with sites like WIChealth.org or the WIC Shopper mobile phone app. The wichealth.org online nutrition education tailors nutrition education to the user’s interest has been shown to be effective at facilitating health behavior change, such as increasing fruit and vegetable intake (Bensley et al., 2011). Users of wichealth.org can access the modules through a computer or any mobile device and upon completion have their benefits remotely loaded to the EBT card (Bensley et. al., 2014). However, mobile apps and online technology have their limitations, for the Children Eating Well mobile app pilot study reported some challenges for parents; including “technical problems with their phone, the app not working properly on their phone, challenges in understanding how to use the app, forgetting that the app is on their phone, and lack of interest” (Hull et al., 2017).

Web and mobile tools specific to WIC eligibility and enrollment are more limited. Other public benefit programs, such as Medicaid and SNAP, have begun to offer more robust online and mobile tools for participants that allow them to easily view the status of their benefits, submit documents, and/or communicate with program staff. This type of tool could help participants respond more rapidly and easily to requests for information and more easily manage their appointments. Moreover, the decrease in required in-person clinic visits is one of the possible rationales for how online nutrition education and communication may increase participant retention in WIC (Neuberger, 2016).

Importantly, the development and application of new technologies is core to quality provision of WIC services and likely to address barriers to retention. Adoption of management information systems (MIS) has enabled WIC SA and LA to enhance administration, financial reporting and electronic benefits transfer (EBT) as well as management of client services from scheduling to education. Moreover, the MIS at the local agency level represents an extensive but underutilized participant database that can identify participants at high risk of early termination and inform policy and intervention strategies.

Click here for resources on project background, promising work, and proposal writing.

References

Au, LE, Whaley, S., Gurzo, K., Meza, M., & Ritchie, LD. (2016). If You Build It They Will Come: Satisfaction of WIC Participants With Online and Traditional In-Person Nutrition Education. Journal of Nutrition Education and Behavior, 48, 336-342.

Bensley, R., Hovis, A., Horton, K., Loyo, J., Bensley, K., Phillips, D., & Desmangles, C. (2014). Accessibility and Preferred Use of Online Web Applications Among WIC Participants With Internet Access.Journal of Nutrition Education and Behavior, 46(3), S87–S92.

Bensley RJ, Anderson JV, Brusk JJ, Mercer N, & Rivas J. (2011). Impact of internet vs traditional Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children nutrition education on fruit and vegetable intake. Journal of the American Dietetic Association, 111, 749-55.

Brusk, J.J. & Bensley, R.J. (2016). A Comparison of Mobile and Fixed Device Access on User Engagement Associated With Women, Infants, and Children (WIC) Online Nutrition Education. JMIR Research Protocols, 5, e216.

Buescher, P., Horton, S., Devaney, B., Roholt, S., Lenihan, A., Whitmire, J., & Kotch, J. (2003). Child Participation in WIC: Medicaid Costs and Use of Health Care Services. American Journal of Public Health, 93(1), 145–150.

Colorado WIC Program. (2015). Texting for Retention Program. Final Report: WIC Special Project Grant, Fiscal Year 2014. Denver, CO: Colorado Department of Public Health and Environment.

Gordon, A., & Nelson, L. (1995). Characteristics and Outcomes of WIC Participants and Nonparticipants: Analysis of the 1988 National Maternal and Infant Health Survey. Alexandria, Virginia: U.S. Department of Agriculture.

Hull, P., Emerson, J., Quirk, M., Canedo, J., Jones J., Vylegzhanina, V., Schmidt, D., Mulvaney S., Beech, B., Briley, C., Harris C., & Husaini. B. (2017). A Smartphone App for Families With Preschool-Aged Children in a Public Nutrition Program: Prototype Development and Beta-Testing. JMIR Mhealth Uhealth. 5, e102.

Hunter, L., Meinzen-Derr, J., Wiley, S., Horvath, C., Kothari, R., & Wexelblatt, S. (2016). Influence of the WIC Program on Loss to Follow-up for Newborn Hearing Screening. Pediatrics, 138(1).

Jackson, M. (2015). Early childhood WIC participation, cognitive development and academic achievement. Soc Sci Med. 126,145-53.

National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine (NASEM). (2017). Review of WIC Food Packages: Improving Balance and Choice: Final Report. NASEM; Health and Medicine Division; Food and Nutrition Board; Committee to Review WIC Food Packages. Washington, DC: National Academies Press.

Neuberger, Z. (2016). Modernizing and Streamlining WIC Eligibility Determination and Enrollment Processes. Center on Budget and Policy Priorities. Washington, DC.

Oliveira, V. & Frazao, E. (2009). The WIC Program: Background, Trends, and Economic Issues, 2009 Edition, ERR-73, U.S. Department of Agriculture, Economic Research Service.

Oliveira, V. & Frazão, E. (2015, January). The WIC Program: Background, Trends, and Economic Issues, 2015 Edition, EIB-134, U.S. Department of Agriculture, Economic Research Service.

Pati, S., Siewert, E., Wong, A., Bhatt, S., Calixte, R., Cnaan, A. (2014). The influence of maternal health literacy and child's age on participation in social welfare programs. Maternal Child Health Journal, 18, 1176-89.

Pew Research Center. (2016). Internet User Demographics. Washington, DC 20036

Rodriguez, A. (2018). SC DHEC debuts new mobile unit to help Upstate women & children. Fox Carolina (Meredith Corporation).

Schultz, D., Shanks, C., & Houghtaling, B. (2015). The Impact of the 2009 Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children Food Package Revisions on Participants: A Systematic Review. Journal of the Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics, 115(11), 1832–46.

Sonchak, L. (2016). The Impact of WIC on Birth Outcomes: New Evidence from South Carolina. Maternal Child Health Journal, 20, 1518-25.

Trippe, C., Tadler, C., Johnson, P., Giannarelli, L., Betson, D. (2018). National- and State-Level Estimates of WIC Eligibles and WIC Program Reach in 2015.

US General Accounting Office. (1992). Early Intervention: Federal Investments Like WIC Can Produce Savings. Document HRD 92-18, Washington, D.C.

Vermont State WIC Program (2017). WIC2FIVE: Using Mobile Health Education Messaging to Support Program Retention. Vermont 2014 WIC Special Project Mini-Grant. Final Report. Burlington, VT: Vermont Department of Health WIC Program.

Virginia WIC Program (2018). Virginia WIC on Wheels. Virginia WIC Newsletter, Virginia Department of Health.

Whaley, S., Whaley, M., Au, L., Gurzo, K., & Ritchie, L. (2017). Breastfeeding Is Associated With Higher Retention in WIC After Age 1. Journal Nutrition Education and Behavior, 49, 810-816.