Pandemic Deaths Are Almost Impossible to Count. He Invented a Way to Estimate Them.

“Schools to Close; 30,000 Are Absent.” “New Cases, Including Sunday’s, 1,650--667 In Counties.”

These Baltimore Sun headlines sound recent, but they are from October 1918, at the onset of the 20th century’s deadliest pandemic. The influenza deaths radiated outward, completely overwhelming hospitals: 3,000 in Baltimore in October alone, later reaching 500,000 across the U.S. No one knew it then, but the pandemic would ultimately kill at least 50 million people worldwide.

When rising influenza deaths shut down Johns Hopkins University for three weeks, students at the new School of Hygiene and Public Health had just begun learning to tally mortality statistics. Health departments had just started systematically collecting birth, death, and disease statistics. But in rural areas with few doctors, most deaths went uncounted and unclassified. Many states had no laws requiring deaths to be registered on standardized certificates—the U.S. Death Registration Area would not include all states until 1933.

Accurate influenza data was difficult to collect under normal conditions; during a pandemic it was virtually impossible. (Even today, official numbers of COVID-19 deaths in the U.S. are likely grossly undercounted.) The influenza deaths outstripped officials’ ability to count them, particularly in dense urban areas. Only after the electron microscope was invented in the early 1930s would scientists confirm influenza was caused by a virus, not a bacterium. With no lab test, influenza was often misdiagnosed as pneumonia.

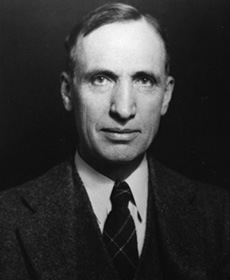

Enter Wade Hampton Frost, a tall, 38-year-old Virginian with pale, deep-set eyes. A physician who excelled in mathematics, field biology, and laboratory analysis, Frost had joined the U.S. Public Health Service in 1905. To track the pandemic’s progression, he and USPHS statistician Edgar Sydenstricker sent teams to conduct house-to-house surveys of 113,000 respondents in a representative sample of communities nationwide. The strategy wasn’t new, but the sample size was huge for its time. Conducted during November and December 1918, immediately after the second wave, the survey recorded age and sex of all household residents, date of onset and duration of any cases of pneumonia or influenza, and date of any deaths.

The surveys revealed a defining characteristic of the 1918 outbreak: the highest mortality was among young adults under age 40, who had no immunity to that season’s deadly flu strain.

To more accurately determine how many people the flu epidemic killed, Frost invented a new method to analyze the survey data. By calculating pneumonia and influenza mortality data from previous “normal” years, he could establish a baseline seasonal mortality, then compare it to the much higher mortality derived from the more precise 1918 survey data. Given the varying reliability across reporting areas, the excess deaths method showed a truer picture of pandemic influenza’s national impact than did the total reported influenza mortality. Typical annual mortality was approximately 1.5 per thousand; the influenza pandemic added another 4 deaths per thousand. This was the first time that the excess deaths method was used to calculate the scope of an epidemic.

The CDC still uses Frost’s method today as it calculates the number of excess deaths from COVID-19, which indicates 57% higher mortality than official reports by doctors, hospitals, and health officials. The excess deaths method also captures mortality indirectly caused by the pandemic, such as patients who could not access care in an overloaded health system.

The 1918 influenza pandemic and its worldwide aftermath jumpstarted the growth of Johns Hopkins into a leading center of research and training in epidemic disease. After the USPHS assigned Frost as a resident lecturer in 1919 and he was named the first chair in epidemiology at an American university, he led the Bloomberg School in pioneering the tactic of teaching students “shoe leather epidemiology”: walking from house to house, block by block to confirm all cases of a disease in a defined area. The pandemic became a primer for Johns Hopkins public health students, including those who had traveled to Baltimore from around the world. All were eager to study the latest methods in public health, particularly in the brand new fields of epidemiology, virology, and immunology, for which the School established the world’s first academic departments.

Karen Kruse Thomas, PhD, is the Bloomberg School historian.