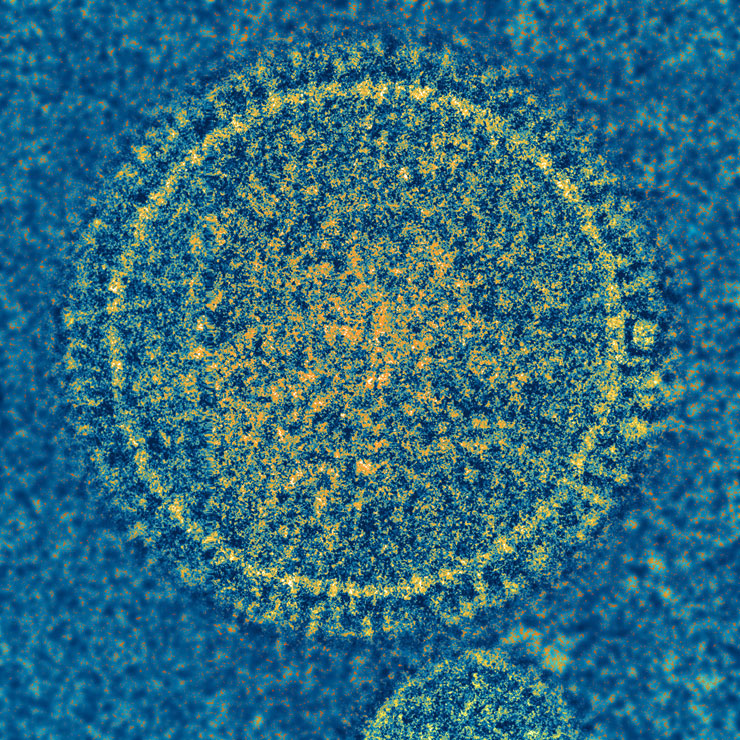

Potential game changer for RSV vaccine development could help millions of children every year

We could be much closer to the development of a vaccine against RSV, the most important viral cause of pneumonia and wheezing illness in infants and young children all over the world.

Professor Ruth Karron talks about why findings from a new vaccine trial she led are so promising.

What does RSV stand for?

Respiratory Syncytial Virus

What does it cause?

It is the most important viral cause of pneumonia and wheezing illness in infants and young children all over the world.

How common is it in kids?

Globally, RSV has been estimated to cause over 3.5 million hospitalizations and between 66,000-199,000 deaths each year. In the United States, RSV is the leading cause of hospitalization in infants. It’s estimated that 10 percent of U.S. children under 5 experience some sort of medical visit for RSV illness every year. Like the flu, RSV can cause fever, a runny nose and a cough. But RSV is more likely than flu to cause wheezing or pneumonia in babies and young children.

Are any treatments effective?

There is no specific drug treatment for RSV and no available vaccine to prevent infection with this virus. This virus was described over 50 years ago and a vaccine has not yet been made.

How are findings from the study you conducted a potential game changer?

I need to give you just a little background so you can see why this is potentially very significant.

Like the chickenpox and measles vaccines, this RSV vaccine is made from a weakened live virus. With this type of vaccine you always have to play a balancing game between weakening the virus and creating a large enough immune response to provide long-term protection from infection. We haven’t been able to reach that balance with RSV after more than 30 years.

But, by eliminating a critical piece of the virus, Dr. Collins and his colleagues at NIH created a very weakened RSV vaccine that still elicits a very strong immune response. Very simply, it makes the virus produce more of the material that the body recognizes as something it needs to fight, and less of the material that allows the virus to reproduce and make people sick. It’s the first time this approach has been taken with an RSV vaccine.

This is the first study to test an RSV vaccine like this one on humans. It could lead to a paradigm shift. We always try to do this dance between weakening a virus and eliciting an immune response. Now we can think about using a virus’s own genetic code against itself. It could be a big step forward in developing a safe and effective RSV vaccine for infants and children. In addition, taking out a relatively big piece of the virus—a whole virus gene— means that it would be very difficult for the vaccine virus to change and to cause disease.

How effective is this vaccine?

In our trial, children who received this live weakened RSV vaccine had a significantly better immune response than children who received another experimental live weakened RSV vaccine in an earlier study. We'll need larger studies to understand how well this vaccine does in preventing RSV disease.

How long might it be until this vaccine is available?

We hope that a live vaccine for RSV will be available sometime within the next decade.

How does this contribute to the goals of the Department of International Health and the Center for Immunization Research?

This is an example of a real global health research initiative. Both the Center and Department try to find ways to improve the global health especially for underserved populations around the world. All children are affected by RSV, but an RSV vaccine could be even more valuable to disadvantaged children in lower-income countries who have less access to hospital care.

This project is also a great example of multiple players coming together to address an important public health concern. Projects like this require a long-term commitment of funding, resources, and expertise, and in particular they depend on long-term support from the federal government. This program is an example of a highly effective collaboration between a research university, government, and industry in pursuit of a vaccine that could substantially improve children’s health here and around the world.

Ruth Karron, MD, is the director of Center for Immunization Research and the Johns Hopkins Vaccine Initiative and a professor in the Department of International Health at the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health. She took some time to answer a few questions about a new study published in Science Translational Medicine that reports the findings from an early clinical trial of a new RSV vaccine.

Learn More

“A gene deletion that up-regulates viral gene expression yields an attenuated RSV vaccine with improved antibody responses in children” was written by Ruth A. Karron; Cindy Luongo; Bhagvanji Thumar; Karen M. Loehr; Janet A. Englund; Peter L. Collins; and Ursula J. Buchholz.

Commentary on the article by Anne Moscona: RSV vaccine: Beating the virus at its own game

The research was supported by NIAID contract HHS 27220090010C, the NIAID intramural program, a grant from the NIH’s National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences (UL1TR000423) and a Cooperative Research and Development Agreement between NIAID, NIH and MedImmune.