Abortion Bans and Infant Deaths

The year after Texas passed its restrictive abortion law, infant deaths in the state increased.

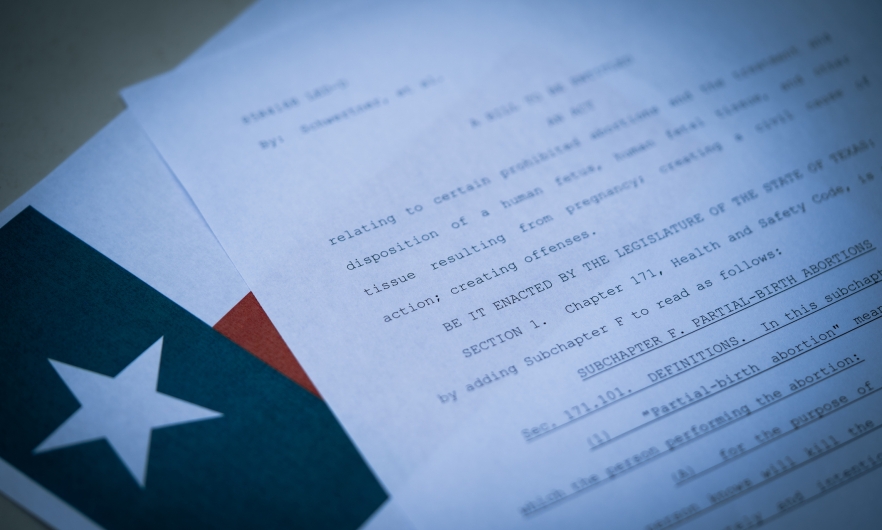

In 2021, Texas passed Senate Bill 8, also referred to as the Texas Heartbeat Act, banning most abortions once a fetal heartbeat can be detected—as early as five or six weeks of pregnancy. Birth certificate data from 2022 show an increase in infant mortality in the state.

Suzanne Bell, PhD ’18, MPH, and Alison Gemmill, PhD, MPH, MA, both assistant professors in Population, Family and Reproductive Health, investigated the connection between the policy and the increase in infant deaths in Texas. Their new study is among the first to show evidence of abortion bans’ impacts.

In this Q&A, adapted from the June 26 episode of Public Health On Call, Bell and Gemmill discuss the study’s key findings—and how other states with severely restrictive laws could also see more infant deaths as a result.

Tell us a little about Texas Senate Bill 8.

Suzanne Bell: Texas Senate Bill 8 went into effect September 1, 2021. It prohibits abortion after the detection of embryonic cardiac activity, which can occur as early as five to six weeks gestation. The bill does not have an exemption for congenital anomalies, which are detected later in pregnancy. At the time SB 8 passed, it was the most restrictive abortion law in the country. This was before the Supreme Court's 2022 Dobbs v. Jackson Women's Health Organization decision.

We have evidence now that SB 8 led to immediate and significant decreases in facility-based abortions provided in Texas, more requests for medication abortion pills to self-manage one's abortion, and greater than expected live births among people residing in Texas, as work Alison and I have done previously demonstrated.

What was your approach and what were the big takeaways of this study?

Alison Gemmill: We used birth certificate data from Texas and several other states to see what would have happened to infant mortality in the absence of this policy. The big takeaway is that we found an unexpected increase in infant mortality in Texas—about a 13% increase—that wasn't observed in the rest of the United States. This suggests that SB 8 was driving this increase in infant mortality.

We saw similar findings with neonatal mortality, which are deaths of infants less than 28 days old. And then we also found, which was a bit surprising, that deaths due to congenital anomalies rose by 23% in Texas, while in the rest of the United States, there was a decrease in these deaths.

Why do you think neonatal deaths from these anomalies increased?

AG: We think that prior to the implementation of SB 8, people who were carrying fetuses diagnosed with severe congenital anomalies had the option to terminate the pregnancy. This option is often exercised when the anomalies are incompatible with life or would result in significant suffering or health complications for the child.

We think that with the restrictive abortion ban in place, birthing people were all of a sudden not able to legally terminate pregnancies, even if severe congenital anomalies were detected, so these pregnancies were likely carried to term. And this probably led to an increase in births of infants with severe congenital anomalies, such as heart defects, neural tube defects, and other life-threatening conditions, who died shortly after birth.

Why did you take up the question of infant mortality? What is the connection with abortion access?

SB: Given that we had observed more births than anticipated in Texas after SB 8 was imposed, we suspected that there could be downstream effects of this policy on infant health outcomes as a result of a few potential mechanisms.

The most obvious is through an increase in deaths involving congenital malformation. As people are forced to continue pregnancies diagnosed with these fetal defects, we might expect to see a greater share of live births experiencing congenital malformations. Congenital malformations are the leading cause of infant mortality in the U.S., accounting for more than 20% of infant deaths.

Abortion restrictions can also lead to greater infant mortality simply as a result of more pregnancies being carried to term, and that’s more infants at risk of death. And the possible increase in financial and emotional stress among pregnant people, as well as a shift in the composition of those giving birth to include more disadvantaged groups who are unable to overcome the barriers imposed by abortion restrictions, may increase exposure to known risk factors for infant mortality.

Even prior to SB 8, there was some evidence of a relationship between abortion restrictions and infant death: States that are hostile to abortion or that have more abortion restrictions had higher infant mortality rates. But these studies were not able to directly attribute this difference in infant death to the policies’ imposition.

You mentioned increased exposure to risk factors for infant mortality. What are those risk factors?

SB: People experiencing unintended pregnancies or pregnancies diagnosed with fetal abnormalities experience greater emotional stress and financial stress, and we know that these may increase risks for infant mortality.

And in the U.S., we know that there are disparities in infant mortality. For example, non-Hispanic Black women have more than two times the rate of infant death than Hispanic and non-Hispanic white women. If these populations are also those most likely to struggle to overcome barriers to abortion, you would see a larger share of births to disadvantaged or minoritized groups, which already are at an increased risk of infant mortality.

Could we expect to see these kinds of impacts in other states that have extremely restrictive abortion access?

SB: I think we could, particularly if we're seeing similar increases in live births in these places as we did in Texas following SB 8.

Right now, 14 states have complete abortion bans with few exceptions for things like fetal anomalies. Another seven states have abortion restrictions pre-viability and in some cases, many weeks before we would even be able to test for congenital malformations, so we would expect to see something similar play out in other settings where abortion has been banned.

Where would you like to take this research next?

AG: There is a lot more to unpack. I think one of the first things we’re going to look at is the impact of Dobbs on infant mortality. And then secondly, we're now getting some data specifically for Texas and others that will allow us to discern whether certain subgroups were more impacted by the policy.

One other thing we will be looking at is morbidity in the infants. We know that infant death is really just the tip of the iceberg. We think there are more infants being impacted by certain types of morbidity that might have lifelong consequences, and we plan to look at that when data become available.

This interview was edited for length and clarity by Melissa Hartman.

RELATED:

- Analysis Suggests 2021 Texas Abortion Ban Resulted in Increase in Infant Deaths in State in Year After Law Went into Effect

- The Consequences of Abortion Restrictions Part 1: Spotlight on Texas (podcast)

- Analysis Suggests 2021 Texas Abortion Ban Resulted in Nearly 9,800 Extra Live Births in State In Year After Law Went Into Effect