How Did Mpox Become a Public Health Crisis?

Yet another virus has escalated to crisis levels in a short period of time. What happened?

As we have seen with other outbreaks, the response is much slower than the virus.

Chris Beyrer, MD, the Desmond M. Tutu Professor of Public Health and Human Rights and director of the Center for Public Health and Human Rights, has been involved in advising the world’s response to monkeypox. As a member of the WHO’s Scientific and Technical Advisory Committee on HIV Viral Hepatitis and Sexually Transmitted Infections, Beyerer and others have been looking closely at the emergence of mpox in the context of changing epidemiology and more evidence of sexual spread.

In an August 3, 2022 episode of the Public Health On Call podcast, Beyrer talks with Josh Sharfstein, MD, about the danger of ignoring health challenges facing the developing world, parallels and differences with the early days of the HIV epidemic, and the future of public health challenges facing societies worldwide.

Public Health On Call

This article was adapted from the August 3 episode of Public Health On Call Podcast.

What is the global picture of mpox right now?

This particular emergence appears to have begun in West Africa about five years ago.

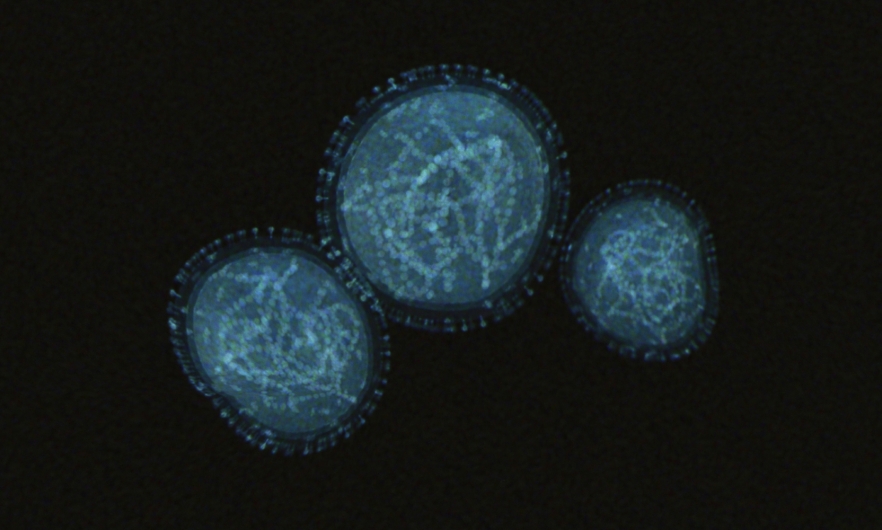

In 2017, there was evidence of this West African clade of monkeypox spreading in Nigerian populations with a differing epidemiology—not with what we've seen in Central Africa, where it's been endemic for many years and where many of the cases are in people with exposure to wild animals, particularly wild rodents. [In those areas], there have been more deaths and more cases in children under five.

But in Nigeria for the last five years, this virus has been spreading with more evidence of what looks like sexual exposure. Unfortunately, this is another example of the world ignoring [a novel outbreak] for five years. [There was] no effort to vaccinate around those cases or to use the tools that we have to contain that outbreak.

Then, [there was] an unclear emergence event in May or perhaps earlier this spring. There were two large gatherings of gay men: a Pride event in the Canary Islands, and a festival in Antwerp, Belgium. Both were gatherings attended by men from across Europe and other countries and continents, and both had outbreaks of monkeypox. Since then, there has been rapid spread.

We now have about 26,000 cases confirmed in more than 76 countries, and only six of them are countries that have endemic monkeypox. Seventy countries where this is not an endemic virus are reporting cases of new spread. That's 98% of the cases.

One of the things that this monkeypox emergence tells us is that the epidemiology of this virus has changed. We don't really know why and how that happened, and we need to know to be able to get control. There is a lot of science and epidemiology to be done here.

And now, it’s been declared a Global Public Health Emergency by the WHO?

That’s right. There was a meeting to look at this emergence when it was in about 30 countries with several thousand cases. At that time, the WHO decided it did not meet the criteria of a global health emergency of international concern. Many of us thought that was a poor decision with how quickly this particular outbreak was spreading and in how many countries.

[In late July], we met again in a very divided meeting. The advisory committee to WHO could not come to a consensus on whether to declare this [and] the vote was pretty evenly divided.

But this is an example where Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus, the WHO director-general, showed leadership: He overruled the committee and decided that it had met the criteria.

What changed with the declaration, and what is the global strategy for controlling this outbreak?

The WHO has a coordinating function—one hopes that those resources will now be focused more on this public health emergency. [The declaration] also gives member states more ability and encouragement to act.

Probably the most important thing is that in this disease emergence—[which is] very different from COVID and radically different from HIV—we already have vaccines that we know work, most of them stockpiled, but nevertheless that can be ramped up for distribution.

There's been a lot of criticism that we've been too slow to do that, particularly in the U.S. During New York City Pride [in June], the city had a testing capacity of about 20 cases a day and very limited vaccine supplies. That allowed New York to become an epicenter of this outbreak, with about 25% of all U.S. cases.

Are there strategies that could eradicate mpox?

I think we have the tools to contain this outbreak, but it's not going well. We were happy that the WHO made that [emergency declaration].

Ideally what you would like to see is very good contact tracing—identification of contacts of people who've been exposed to or who are in sexual or social networks with monkeypox cases. But in Europe, [we’re seeing] a number of cases that don't appear to be epidemiologically linked. That means there's more community transmission than we think—which is also the case in the U.S.

Smallpox—a closely related, though much more lethal virus—was controlled and eventually eradicated through ring vaccination. [Ring vaccination is] vaccinating all the contacts and communities around a known case. That’s probably going to be important [going forward].

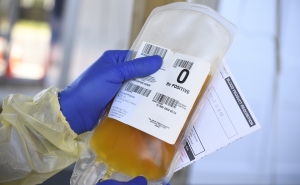

Right now, we're using the monkeypox vaccines that we have. The two-dose Jynneos vaccine is safe and effective, including in people who are immunocompromised. The smallpox vaccine, ACAM2000, is a live vaccine and not safe for people who are immunocompromised or who have HIV.

When you have an epidemic that is primarily spreading in gay and bisexual men, you have to think about how many of those people have HIV—about 15% of all gay men worldwide are living with the HIV virus. We can’t use the existing smallpox vaccine for that population, but we can use the JYNNEOS monkeypox vaccine, which is manufactured in Denmark. The U.S. owns a significant amount of that vaccine, and we've been slow to start using it.

With vaccines, with contact tracing, and with good epidemiology, we could contain this. But right now, as we have seen with other outbreaks, the response is much slower than the virus. The virus is ahead of us.

The initial cases in this emergence have predominantly been among men who have sex with men. Do you see this as a potential obstacle to messaging in the control of mpox?

It's a very important question.

This is yet another virus that has emerged from the Central African rainforest—the same area as HIV. It has a horribly stigmatizing name. It's not actually a “monkey” virus. It's called monkeypox because one of the first major outbreaks was identified in a monkey facility where the animals became infected with a rodent virus.

Although “rodentpox” wouldn't be much less stigmatizing, it is overwhelmingly spreading in networks of men who have sex with men right now. Nobody should sugarcoat that. That is the reality. But, it is unlikely that it will stay there.

Think, for example, about the emergence that we saw of MRSA—methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus—[which] started in networks of men who have sex with men. It very quickly [spread] because, like monkeypox, it’s a disease of close skin-to-skin contact that doesn't have to be sexual. We had outbreaks in athletes. It became endemic in prisons and jails because of hygiene issues and skin-to-skin contact.

[Monkeypox] does have the potential for a wider spillover. Nevertheless, right now the focus has to be on men who had sex with men.

I've been on a number of calls with the White House, the CDC, and LGBTQ+ community and advocacy groups. The White House convened very quickly with its office of LGBTQ+ outreach. They are worried about stigma issues and thinking about how to address them.

The administration, CDC, and the WHO are trying to strike the balance between being realistic about this outbreak and where it's spreading without stigmatizing. That is not easy to do.

When you get down to the local level, these questions are going to be particularly important. State and city health departments, for example, are the places people will go to seek testing and vaccination. So far, [anecdotal evidence] at the local level suggests that it hasn't been a terribly stigmatizing experience. But there have been people with clear risks who have been honest about their exposures and found it very hard to get tested.

And, the two-step testing is onerous. People didn’t want to get tested, because [first] there's a screening test for orthopoxviruses, and then there's a confirmatory test. Until very recently, only the CDC could do that confirmatory test. For a provider, it was an arduous process with a lot of paperwork. That certainly hindered our testing.

How do you thoughtfully advise people, with regard to precautions?

For many gay men, this is an echo of what was happening with the early spread of HIV, when safe sex messaging was, “People need to use condoms. Maybe consider reducing the number of partners.” Eventually, [there was] the very contentious battle over closing bathhouses in New York City, for example, which is playing out again.

There are recommendations from the CDC about how to participate in raves and group activities that may involve close bodily contact. The bad news is that condoms do not protect against monkeypox, because it spreads through skin-to-skin contact, not just genital contact. You don't have the same messaging, but it is really important for people to consider their own risk taking. [Many] gay men are saying that now is not the time for this kind of partying, particularly while vaccines are in such short supply.

Do you see the failure to deliver tests and vaccines as a weakness in the mpox response?

There's no question that that will be a real challenge and a concern if the monkeypox virus spreads beyond the networks it is in now. Our best opportunity for achieving control and ending this outbreak is while it is concentrated in men who have sex with men. I say that because the LGBTQ+ community has a long record—because of HIV and because of COVID—of resilience in the community. There's a lot of public health experience and vaccine rates are much higher. Recently, for example, New York City has been out bringing monkeypox vaccines to gay communities on Fire Island and there were lines are around the block. But [there aren’t enough vaccines] to meet demand. If we can contain this before we get wider spread, that is our best shot.

We also don't have and have not seen the same kinds of vaccine hesitancy in the LGBTQ+ community that you see in a number of other communities. There are many people in the LGBTQ+ community who have public health and medical expertise. In that sense, we are quite less marginalized than many other communities. I think the fact that, certainly for gay men of my generation, this is our third pandemic, means we are a community that is very seasoned, and has a lot of ability to take care of our own.

Chris Beyrer, MD, MPH ’91, is the Desmond M. Tutu Professor of Public Health and Human Rights and director of the Center for Public Health and Human Rights at the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health.

Joshua Sharfstein, MD, is the vice dean for Public Health Practice and Community Engagement and a professor in Health Policy and Management at the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health. He is also the director of the Bloomberg American Health Initiative and a host of the Public Health On Call podcast.

Related:

- What You Need to Know About Monkeypox

- “Dangerously Unprepared”: Jennifer Nuzzo on the Global Health Security’s Newest Findings (Public Health On Call)

- A Conversation With a Monkeypox Patient (Public Health On Call)