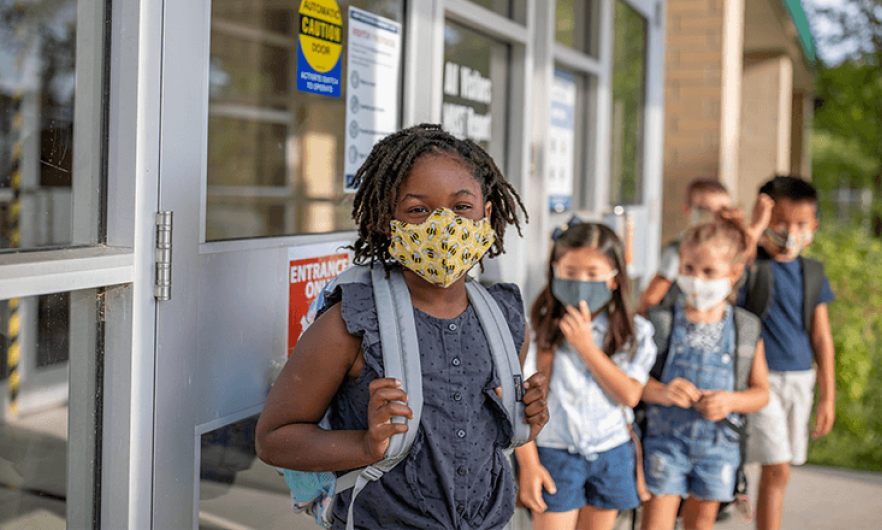

Outbreak, Interrupted: Why Testing Is Important for K-12 Schools

Combined with other public health interventions, COVID tests can help keep K-12 schools safe for everyone.

INTERVIEW BY MELISSA HARTMAN

In March, the Biden administration announced that it would direct $10 billion from the American Rescue Plan to expand testing in schools.

What might this expanded testing entail? How does school testing actually work? In this Q&A, Gigi Gronvall, PhD, an associate professor in Environmental Health and Engineering and a senior scholar at the Center for Health Security, explains how testing programs might be scaled up, why they’re an important part of a COVID-prevention strategy, and how they might help prevent other diseases in the future.

When the Center for Health Security report came out in October with recommendations for testing in schools, there were still a lot of unknowns about kids and COVID and transmission. Do we know more now?

I would say no—at least nothing that makes a practical difference. From the numbers, schools don’t appear to be focal points for transmission. Kids have similar viral loads as adults, but most of the benefit is that they don’t seem to have this severe illness, or anywhere near as severe as adults. It seems that transmission in schools is lower than community transmission, but is that because of the mitigation measures? Is that because the kids are generally more compliant with masks than maybe adults are? That’s unclear.

Have you seen new options for testing that might make more frequent testing in schools a realistic option now?

We recently had a webinar on school testing with a testing company called Gingko. It was interesting how Gingko expanded their capacity for testing by finding local laboratories to work with, so they’re not trying to ship all the samples back to Boston [where their labs are headquartered]. The samples are collected once a week and go to a local lab, which gives more timely information than if they were being shipped. Students do the swabs themselves, and then they put their samples in a pooled test.

This way they could collect samples by classroom, quickly get through the school, test lots of samples, and quickly get results. I don’t think all the testing companies have the same methodology. The perfect situation would be to have testing all the time, but you can’t have that practically. You can’t have that financially so everything is going to be some step away from that ideal state of having perfect information all the time. We’ll have to see what the other testing companies are doing, but probably once a week is what most companies are doing if they’re doing testing. It’s what universities are doing if they’re having testing.

You mentioned pooled tests. So, basically, a pooled test will tell us if there’s virus transmitting in a population, in this case a classroom. So what if it’s found in pooled testing? What happens after that?

Some sites will then quarantine the whole class and recommend that some individuals get tested. Others will have the rapid test right there to identify which person is infectious. There are a lot of different ways that you could go about that next step, but it’s not practical to test everybody every day. Doing pool testing once a week is how you get the cost to under $10 a student. I think Gingko said it’s something like $6 a student for their methodology. Otherwise, it would just be much more cost-prohibitive.

In a lot of places, like here in Maryland, educators and school staff are a priority group and a lot are being vaccinated. So let’s assume that in a school, most of the adults have been vaccinated. Would they still need to participate in testing?

It’s still a recommendation on the CDC website. Say I am vaccinated and I get exposed to somebody who has COVID and get it myself. My immune system is working on fighting that virus, and I don’t even know I’m sick. But maybe I’m producing a little bit of virus. If I had the potential for exposure, I should think twice about going to a nursing home, for example, where there might be some unvaccinated people, just to be on the safe side.

I think there are other factors involved in doing pool testing as a class, and the teacher modeling behavior might be just as valuable as that $6 spent on a test. It might not be absolutely necessary but I could see a teacher saying, “Now it’s time that we all do this,” and apparently different classes have come up with songs and things like to go along with the testing and how long they do the swabbing.

I think a lot of people see vaccines rolling out and think, “Okay, that’s going to get us to the next level of ending the pandemic.” Why would testing in schools still be important?

Not everybody has been vaccinated. We still have quite a lot of people who are transmitting virus. There are lot of people with COVID, and there’s a lot of exposure happening. We’re not going to get to the point where it becomes a rarity for a while.

I don’t know what the future of testing in schools is going to be, but I would like to see this expanded to prevent a disease that does affect kids much more: I would love to see flu be something kids are tested for in the future. If the systems are put into place [for COVID], we could use them to try to limit the spread of flu and other diseases in schools. Flu does kill kids at a much higher percentage and causes a lot of serious illness and kills adults, too. And there is a lot of transmission that goes on in schools.

I am hoping that people see the value in this and that we can take a little bit more aggressive action when it comes to reducing illness overall.

The funding from this COVID relief package is a good chunk of money, but money isn’t everything. What do you see as the main barriers to having effective testing programs widely in schools?

Because everything is so decentralized, making changes relies upon individual leaders at local levels taking action. That’s part of the reason that on our Testing Toolkit website, we list several different testing services. We have a curated list where people could say, “Okay, I need a testing service for K through 12. So the test needs to work in children and it needs to have results in this amount of time and this amount of capacity.” This website gives them a place to start if they’re not partnering with a local university or lab to do some of this work.

How fast do the results have to be to make sense for schools?

Everything is some step away from the ideal. The ideal would be that you test and right away get the result. But there is a problem with scaling that, and there is a problem with cost. Perhaps a rapid antigen test would be useful in some places, but a scaled way to use PCR to get results in less than 24 hours is pretty good. You just don’t want to get to the point where you’re waiting days, because then by the time you find things out, everybody’s been exposed—and then you have a much bigger problem.

Is there anything about testing that you think people might not know or maybe misunderstand?

The whole idea of testing can be pretty confusing. There are lots of different tests; they have different parameters and give different kinds of results. One thing people should know is that if you’re vaccinated and you test positive, you probably have COVID. The vaccines prevent serious illness, not infection. Nothing in the test is going to pick up the vaccine; it’s only going to pick up a natural infection. I heard a reporter who said that they were hearing people say, “Well, I tested positive, but I’m sure it’s a false positive because I’m not feeling sick.” That’s just not how this works. You can be asymptomatic and still be infected. Kids can be transmitting when they show no illness at all. In fact most of them won’t show symptoms.

If kids can transmit to their parents, for example, it seems like testing is a good measure to protect the whole community. I mean, if it’s determined that virus is transmitting in a kid’s class, there are implications for the kids’ families and their contacts, too.

Exactly. Because not everybody is going to have been vaccinated, it’s still important to do the testing. And that’s not the only thing. All of the things we’re doing—between masking, air ventilation, testing, social distancing—are important, so you can’t hold testing out as being the only thing we need to be doing. But it’s still important, and I think it is going to be important for some time to come.

Melissa Hartman is managing editor of Hopkins Bloomberg Public Health magazine.