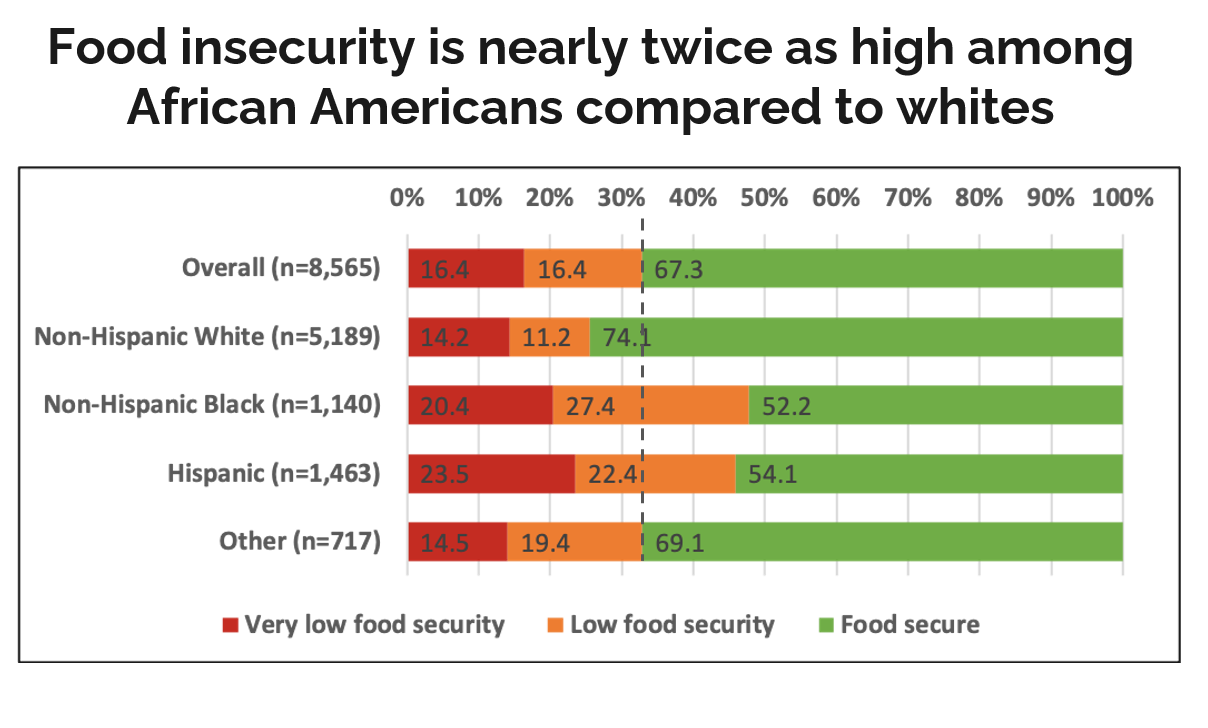

Nearly Half of Black and Hispanic People in the U.S. Face Food Insecurity, New Study Finds

Results from the National Pandemic Pulse Project survey found widespread food insecurity—limited or uncertain access to enough food for a healthy diet in the past 30 days—across the U.S. The nationally representative survey was led by researchers at the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health and conducted between December 15 and 23, 2020.

Source: National Pandemic Pulse 2020

Overall, a third of survey participants reported being food insecure. Rates, however, were nearly twice as high among Black (48%) and Hispanic (46%) people compared to white (25%) respondents. These rates are well above the 10%–12% average experienced in the country over the past 20 years. Even during the Great Recession of 2008 and 2009, national food insecurity rose to only 15%.1

The racial and ethnic disparities uncovered in the survey are not new. Since 2001, food insecurity for white people has ranged from 8% to 11%. It has sometimes been as much as three times higher for Black people (21%–26%) and Hispanics (16%–27%) over the same time period.

The survey also found that government support was not reaching those most in need. Four in ten food insecure individuals had not received any social safety net benefits, such as SNAP (Supplemental Nutritional Assistance Program), in the past 30 days. Only half of respondents with very low food security reported receiving any free meals or groceries within the last 30 days.

“We are seeing crisis levels of food insecurity associated with the pandemic. Communities already vulnerable and struggling are being disproportionately affected,” says Julia Wolfson, PhD ’16, MPP, survey co-lead and an assistant professor in the Department of International Health at the Bloomberg School. “We need a coordinated and comprehensive plan to get food quickly into the hands of the people who are at the greatest risk of going hungry. This includes making sure that SNAP benefits are available to all who need them and are sufficient to purchase enough healthy foods throughout the month.”

The pandemic is also hitting minority communities harder economically. The survey found that 27% of Black people and 31% of Hispanics reported losing a job or half of their income due to the pandemic in the past year, compared to 17% of white respondents. Of those people who reported losing a job or half their income, 70% were food insecure.

“Extraordinary measures are needed to deal with the unprecedented levels of food insecurity in the country,” says Wolfson. “Food insecurity has serious adverse health consequences in both the short- and long-term, including poorer mental health, worse diet quality and nutrition, and higher rates of chronic diseases such as diabetes. It’s critical for the federal government to tackle these longstanding racial disparities in food security that have been exacerbated by the pandemic. Policies that address structural racism and barriers to economic and food security are needed. Increasing SNAP benefits by 15% and raising the minimum wage to $15 an hour would be a good start.”

This was the second of six surveys planned by the National Pandemic Pulse Project. The next round is scheduled for March 2021 and will also track levels of food insecurity.

“The data is clear,” says Alain Labrique, the project lead and a professor in the Department of International Health at the Bloomberg School. “The U.S. COVID-19 pandemic has caused over 500,000 tragic deaths, but also a wave of societal disruption that will have consequences far into the future. These estimates of food and job insecurity reveal a stark picture of deep inequities in this country, worsened by the pandemic, with public health, political and economic ramifications that are only just being understood."

Food insecurity was measured using the same six questions in the USDA’s Household Food Security Survey short-form. Questions assessed concerns about running out of food, skipping meals, going hungry, and not being able to afford food in the previous 30 days. Respondents were grouped into one of three categories: food secure, low food security, or very low food security. People who had very low security lacked money or resources to buy enough food for a healthy diet. Those with low food security had reduced the quality, variety, or desirability of the foods they purchased and were worried about being able to afford enough food in the future. Food secure respondents had no anxiety about or problems with buying food.

The survey included over 8,500 respondents and results can be analyzed by race and ethnicity, age, gender, education, and income for each U.S. Census region. The National Pandemic Pulse Project is funded by the Johnson & Johnson Foundation and aims to better understand the disproportionate effects of the COVID-19 pandemic among low-income and minority communities in the U.S. In addition to questions about food insecurity, the second round survey included questions about risk perceptions of COVID-19, pregnancy experiences, pandemic anger, trust in science, vaccine hesitancy, COVID-19 testing access, economic distress, and mental health. Findings are preliminary and further analysis is being conducted. To learn more, visit the project’s website and read the policy brief on food insecurity.

Other Johns Hopkins faculty and students working on the National Pandemic Pulse Project include Smisha Agarwal, PhD; Prativa Baral, MPH; Jeffrey Edwards; Daniel Erchick, PhD; Dustin Gibson, PhD; Madhu Jalan, MS, MBA; and Alex Zapf, MSc, MSPH