Infectious Disease Experts Recommend Using Antibodies from COVID-19 Survivors as Stopgap Measure to Treat Patients and Protect Healthcare Workers

Infusions of antibody-laden blood have been used with reported success in prior outbreaks, including the SARS epidemic and the 1918 flu pandemic

Countries fighting outbreaks of the novel coronavirus disease COVID-19 should consider using the antibodies of people who have recovered from infection to treat cases and provide short-term immunity—lasting weeks to months—to critical health care workers, argue two infectious disease experts, including Arturo Casadevall, MD, PhD, Alfred and Jill Sommer Professor and Chair of the Department of the Molecular Microbiology and Immunology at Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health.

In an essay published online today March 13 in the Journal of Clinical Investigation, Casadevall and Liise-anne Pirofski, MD, chief of the Division of Infectious Diseases at the Albert Einstein College of Medicine, write that the infusion of antibody-containing serum from convalescing patients has a long history of effective use as a stopgap measure against infectious diseases, and can be implemented relatively quickly—long before antiviral treatments, monoclonal antibodies, and vaccines are developed, approved and available. The paper is available here.

“In addition to public health containment and mitigation protocols, this may be our only near-term option for treating and preventing COVID-19, and it is something we can start putting into place in the next few weeks and months,” Casadevall says.

To date, the novel coronavirus SARS-CoV-2 that appears to have originated in Wuhan, China, in late 2019 has caused outbreaks of COVID-19 across the world. As of March 12, there were 125,048 officially confirmed cases in 118 countries and 4,613 deaths from pneumonia caused by the virus, according to the World Organization’s Situation Report. Researchers now are expediting efforts to design and/or test potential treatments and vaccines. However, as this is a new coronavirus, none is likely to be available within the next several months. And a vaccine is unlikely to be available in less than one year, perhaps longer.

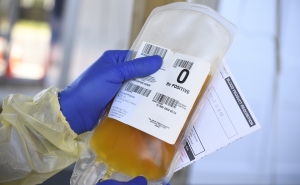

Physicians have long known that patients tend to make large numbers of antibodies against an infecting pathogen. These antibodies circulate in the blood of survivors for months and years afterward, and usually have the potential to bind to the pathogen and neutralize its ability to infect cells. The procedure for isolating serum, the fraction of blood containing antibodies, is also a long-established technology and can be performed using equipment normally found in hospitals and blood-banking facilities.

In this instance, individuals who recover from COVID-19 and are still in their convalescent phase would be asked to donate serum containing the antibodies that would then be processed for injection into sick patients and in those exposed to SARS-CoV-2. Because of the ease of the technique, the many reports of its apparent effectiveness, and the basic plausibility of how it works, doctors once commonly used “convalescent sera” to treat patients or immunize persons at high risk of when there was otherwise no defense against a pathogen—in outbreaks of measles, mumps, rubella, polio, and even the 1918 flu pandemic.

The practice, widespread before 1950, was curtailed after clinicians recognized that donor blood may contain other live pathogens and inadvertently spread disease. Today’s blood bank technology is much improved, with routine screening for pathogens such as hepatitis viruses and HIV, so the use of this method is now considered as safe as an ordinary blood transfusion, Casadevall says.

Moreover, serum from convalescing patients continues to be used in cases where doctors have no other good options. It was employed in the 2002–04 SARS epidemic, in several bird flu and swine flu epidemics, in an Ebola virus outbreak in Africa in 2013, in a recent outbreak of another coronavirus-caused disease called MERS, and even in the early stages of the COVID-19 outbreak in China. In these cases, doctors have used the method on small groups of patients and without the usual clinical trial protocols. However, their reports suggest that the technique has an acceptable level of safety and is usually somewhat effective at reducing the viral burden and improving patient outcomes, especially when applied early in the disease course.

It is so far unclear how many patients who have recovered from COVID-19 would be needed to supply antibody-filled serum to treat a single infected patient or provide immunity to a single at-risk person. Casadevall says, however, that a little could go a long way if used for preventing infection or for treating infection in the early stages when the viral load is lower.

“How many patients you can help, per volume of convalescent serum, will depend on how you use it,” he says. “And we’ll have to put protocols in place to make sure that the use of this sera is safe. But we’re not talking about research and development—this is something that physicians, blood banks, and hospitals already know how to do and can do today.”

Casadevall and other physicians are now trying to establish the practice of using convalescent sera as a preventive and treatment for COVID-19, in specific U.S. hospital networks and ultimately nationwide.

“The Convalescent Sera Option for Containing COVID-19” was written by Arturo Casadevall and Liise-anne Pirofski.

# # #

Media contacts for the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health: Kathy Marmon at 410-562-6005 or kmarmon@jhu.edu and Barbara Benham at 410-614-6029 or bbenham1@jhu.edu.

For more information on the novel coronavirus and COVID-19, visit our COVID-19 Expert Insights site.