How the Bloomberg School Enforced the Color Line in Admissions—And Then Broke It

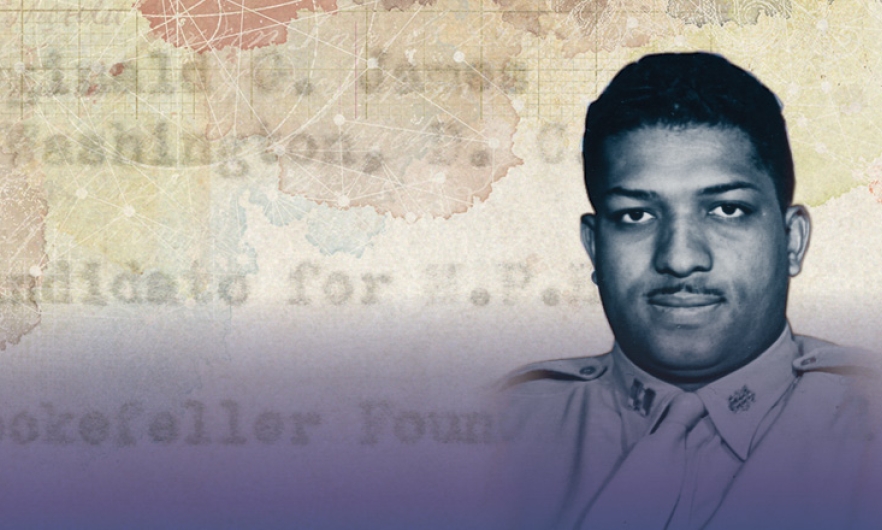

Reginald G. James (MPH 1946) was the first Black student admitted to the Johns Hopkins School of Hygiene and Public Health (now the Bloomberg School of Public Health) and also the first Black graduate of Johns Hopkins University.

An excerpt from Health and Humanity: A History of the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health, 1935–1985

Editor’s note

The excerpt below is the first of two from the published book Health and Humanity: A History of the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health, 1935–1985. We are publishing these excerpts on our School website as part of our commitment to Inclusion, Diversity, Anti-Racism, and Equity. In order to shape a more equitable and just future, we feel it is important to acknowledge our own past. These excerpts will be followed by additional articles on the current affairs of racism and public health and stories of our School’s research and efforts aimed at creating a better future.

B. M. Rhetta, a Black physician who was president of the Monumental City Medical Society and chairman of the Baltimore Interracial Commission, had been applying unsuccessfully to study public health at Johns Hopkins since 1922.

The leaders of the School of Hygiene and Public Health (now the Bloomberg School of Public Health) embraced the lofty goals of improving health in Baltimore and beyond, but also upheld Maryland’s racial segregation laws, which barred Black residents from white state universities. Since no in-state colleges for Blacks at the time offered graduate or professional degrees, African Americans had to leave Maryland to pursue advanced education. From its inception, JHSPH had admitted a multiethnic student body that included physicians from Latin America, Europe, and East and South Asia. But Johns Hopkins University remained firmly closed to Blacks, who in the South could only attend segregated colleges with inferior funding, libraries, and research facilities.

Rhetta finally saw glimmers of hope on the horizon in April 1938, when he met with Johns Hopkins president Isaiah Bowman. The University of Michigan had recently become the first US school of public health to admit a Black student, Paul Cornely, who earned a DrPH in 1934 (he went on to become the first Black president of the APHA in 1968). Closer to home, the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) Legal Defense Fund, led by Baltimore’s own Thurgood Marshall, had won in Murray v. Maryland (1936), which forced the University of Maryland Law School to admit the Black plaintiff. Marshall and the NAACP would continue to push for the integration of the School of Nursing and other professional schools at University of Maryland’s Baltimore campus.

President Bowman, although he was Canadian, was openly segregationist and anti-Semitic. Rhetta informed him that the Harvard School of Public Health had just accepted a Black Baltimore physician, H. Maceo Williams, and that therefore Johns Hopkins should consider admitting qualified Black physicians to the one-year Certificate of Public Health (CPH) program. Postgraduate education was extremely difficult to obtain for Baltimore’s Black health professionals, who could not work or train in hospitals that cared for white patients, even facilities with separate “Jim Crow” wards, such as Johns Hopkins Hospital. But under the slogan “germs know no color line,” southern health departments, including the Baltimore City Health Department (BCHD), began to enlist Black doctors, nurses, and laypeople to extend public health programs into the Black community. City Health Commissioner Huntington Williams (DrPH ’22), who had written Maceo Williams’s recommendation letter for Harvard, pledged his support for four more Black physicians to apply to the Hopkins CPH program. But Black applicants always received the same rebuff from the school’s Advisory Board: the Maryland General Assembly made a small annual payment to the university, and therefore Johns Hopkins was a state-supported institution obliged to follow segregation laws. In fact, private universities such as Johns Hopkins were free not to discriminate because they were not bound by the Constitution’s guarantee of “equal protection under the law,” which only applied to government-supported institutions. In nearby Washington, DC, Black graduate students attended American University and the Catholic University of America.

Two JHSPH deans who read Rhetta’s letters lobbying for admission were sons of the Old South. Wade Hampton Frost, dean from 1931 to 1934, was named after Wade Hampton, the Confederate brigadier general under whom Frost’s father had served in the Civil War. During Reconstruction, Hampton had been elected governor of South Carolina with the violent assistance of the Red Shirts, a paramilitary group formed to help the Democratic Party wrest the state from Republican control by disrupting elections and brutally intimidating Black voters, sometimes by resorting to murder. Allen Freeman, dean from 1934 to 1937, was the son of General Walker Burford Freeman, the honorary commander-in-chief of the United Confederate Veterans; Freeman’s brother, Douglas Southall Freeman, edited the Richmond News Leader and authored the definitive multivolume biography of the Confederacy’s premier general, Robert E. Lee. Bowman, Frost, and Freeman, therefore, were disinclined to challenge Johns Hopkins’ whites-only admissions policy for US students. The Advisory Board even denied admission to a Black physician preparing for service in the Ethiopian Ministry of Health. The single exception to the pre-1945 exclusion of Blacks from JHSPH was in 1933, when Marjorie A. Forte and Myrtle M. Patton, the only two Black public health nurses practicing in Maryland, joined 50 white nurses at a one-day Institute of Hygiene hosted by JHSPH.

In November 1938, the US Supreme Court ruled in Missouri v. Gaines that the constitutionality of segregation laws rested “wholly upon the equality of the privileges which the laws give to the separated groups within the State.” If none of a state’s public universities agreed to admit Blacks to graduate and professional programs offered to whites, then the state government would be obliged to build new separate schools for Blacks that were demonstrably equal to those for whites. Although Johns Hopkins’ faculty was then all white, the Gaines decision prompted Broadus Mitchell, a political science professor, to mount a public critique of the university’s segregationist admissions policy. He charged that by excluding Black students, Johns Hopkins was “turning our backs on the part of the population that needs us most,” citing the racial disparity in Baltimore’s mortality rates. Mitchell took aim at the School of Hygiene’s international reputation to reinforce his point. “The Caroline Islands have our solicitude before Caroline Street Baltimore,” he declared, “and the Dutch East Indies before Druid Hill Avenue.”

After Maceo Williams graduated from Harvard, he returned to Baltimore and became the first African-American doctor to join the BCHD staff on a full-time basis. From 1939 to 1966, he served as the founding director of the Druid Hill Health Center in West Baltimore, the city’s first neighborhood clinic for Black patients. Among his first tasks was to assist JHSPH with obtaining the cooperation of Black East Baltimore residents for a major public health survey in 1939. The move to bring Maceo Williams on the BCHD staff was part of a larger movement by health departments to address Black health needs in response to the growing influence of the medical civil rights movement, but the BCHD still would not allow a Black physician to treat white patients.

When World War II began, news of high rates of syphilis among recruits revived fears from World War I that sexually transmitted infections, then called venereal diseases, or VD, would impede the fighting effectiveness of the armed forces. With manpower at a premium, the War Department assigned VD control officers to all major Army detachments, and Johns Hopkins stepped in to supply trained physicians. The national syphilis campaign and the civil rights movement both accelerated during wartime, prompting the School of Hygiene finally to admit its first African-American student, Reginald G. James (MPH 1946), who would also be the first Black graduate of Johns Hopkins University. James, a US Public Health Service (PHS) officer and Rockefeller Foundation fellow, had assisted the Alabama State Health Department in its VD survey and treatment program in rural Macon County, the home of Tuskegee Institute. He was certainly well qualified, but James succeeded where qualified Black applicants had failed previously because the PHS and the school considered him a strategically valuable partner in the campaign against syphilis among Blacks in the armed forces and the South.

After James received his MPH in 1946, he returned to active duty in the PHS and JHSPH began admitting African Americans to all its degree programs. By contrast, Black students were not admitted to the Johns Hopkins Hospital School of Nursing until 1952 or as candidates for the MD until 1963. Despite JHSPH’s international diversity during this era, by 1961, the school had awarded degrees to only five Black men and one Black woman. Nationally, the only school that produced significant numbers of African-American public health graduates was North Carolina College, a Black state school that, in partnership with the University of North Carolina School of Public Health, awarded more than 100 bachelor’s degrees to health educators.

Karen Kruse Thomas, PhD, is the Bloomberg School historian.

“Health and Humanity: A History of the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health, 1935–1985” by Karen Kruse Thomas is available in its entirety for purchase or download here.

Related

Racism: A Public Health Crisis