Can commercial video games be good for you?

SEVERAL CONTROLLED STUDIES SHOW GAMES LIKE TETRIS AND BEJEWELED MIGHT HELP, BUT MAJOR CHALLENGES MAKE REVIEWING THE EVIDENCE DIFFICULT

A new study led by researchers at the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health makes a case for the potential health benefits of commercial video games. The study, published recently in Frontiers in Psychiatry, calls for a strategic investment in a research agenda to develop standardized research protocols and to promote new collaborations between academia, gaming communities, and private sector developers.

"Video games are extremely popular,” says Michelle Colder Carras, lead author and a recent postdoctoral fellow in the Department of Mental Health at the Bloomberg School. “If we can systematically determine aspects of games or gaming communities that provide health benefits, we have the potential to leverage video games to make a big impact on population health.”

The article reviews instances in which games have been shown to be useful in several areas of public health and medicine. For example, success in playing the computer solitaire game FreeCell may be useful to monitor cognitive status in adults with mild cognitive impairment, and puzzle games such as Tetris have been shown to reduce depression, stress, and even prevent flashbacks after a traumatic event.

The researchers point to a major limitation of gamified health interventions: they often do not maintain interest the way a game would, which means that once users realize that the “game” they are playing is actually something healthy, they would spit them out like "chocolate-coated broccoli."

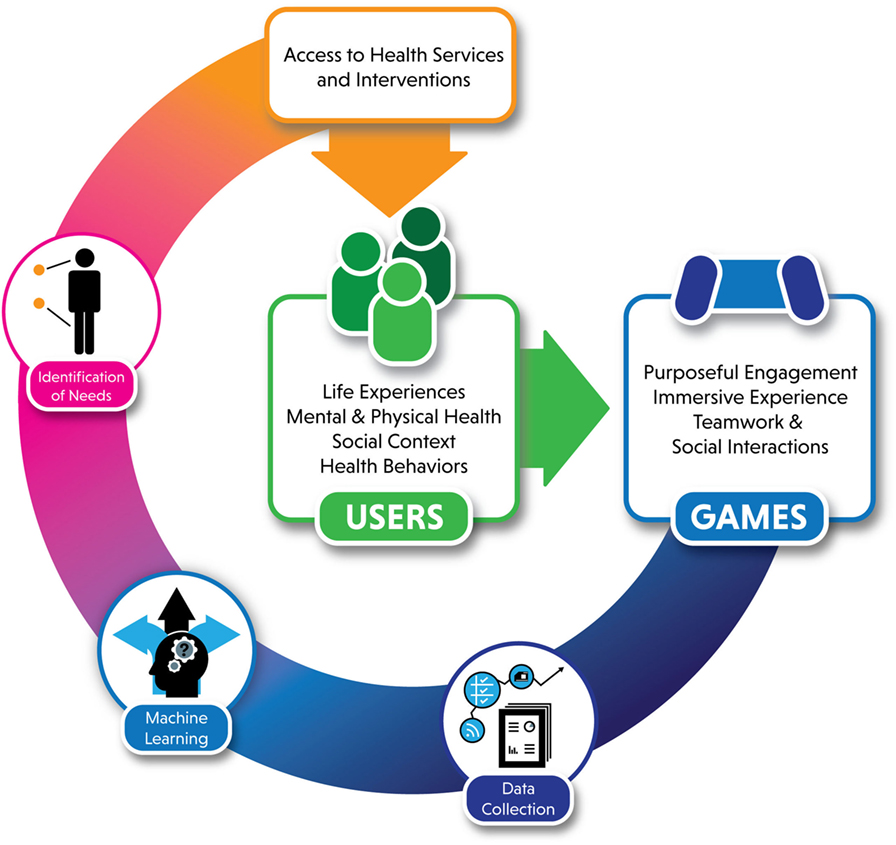

Conceptual framework for video games as therapy

However, there are quite a few obstacles to overcome in order to make progress in the study of using existing commercial games for therapeutic purposes. “There’s a bit of a moral panic around video games, especially in public health,” says Colder Carras. “Commercial games are seen as exposures that create risks to health and lead to problems like violence, obesity, or addiction. There may even be be some publication bias against positively slanted articles in high-quality scholarly journals.” The paper suggests that this overall negativity within some areas of health research also seems to affect the terms scientists and clinicians use to talk about games—for example, calling a program that makes use of the Microsoft Kinect controller an “interactive digital rehabilitation technology” instead of a video game.

“When you combine those challenges to finding or publishing articles with the incredibly rapid pace of change in games and gaming technologies, you have the potential for missing out on a lot of potential good,” says Colder Carras.

“We designed this article to be a challenge to the scientific community to invest the time and resources into moving forward with a research agenda in a systematic way,” says co-author Alain Labrique, associate professor in the Department of International Health the Bloomberg School and Director of the JHU – Global mHealth Initiative. The team—which, in addition to the Bloomberg School, includes researchers from Trimbos Institute, University of Southern California, Harvard and Nottingham Trent—is currently working on developing partnerships that will promote this research agenda and welcomes input from the Hopkins and wider community.

Commercial Video Games As Therapy: A New Research Agenda to Unlock the Potential of a Global Pastime was written by Michelle Colder Carras, Antonius J. Van Rooij, Donna Spruijt-Metz, Joseph Kvedar, Mark D. Griffiths, Yorghos Carabas and Alain Labrique. The article is available for free at https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2017.00300.