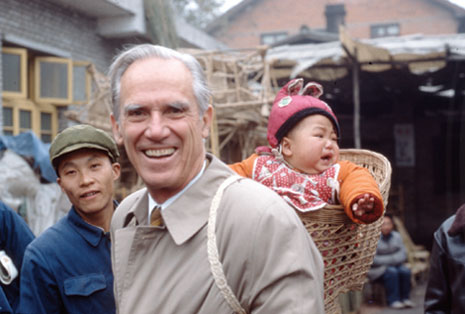

Carl E. Taylor 1916-2010

Watch Video

Read Tributes

Carl E. Taylor, MD, DrPH, founder of the academic discipline of international health and a man of spiritual conviction who dedicated his life to the well-being of the world's marginalized people, passed away February 4 from prostate cancer. He was 93. The reach of his life was extraordinary, personally working in over 70 countries and having students from more than 100 countries. He was sharing this near century-long perspective with his students up until a week before his death.

Taylor was born in the Indian Himalaya to medical missionaries. His career began at age 7 as a pharmacist assistant in his parents’ oxcart-based clinic in the Indian jungles. His childhood was spent in those jungles, before going on to earn his medical degree from Harvard. (His medical school application opened with, “My study of anatomy began dissecting a tiger to see where the food went.”) Following medical school, he worked in Panama where he married his wife of 58 years, the late Mary Daniels Taylor, who died in 2001 and was professor emeritus of Education at Towson University.

Taylor returned to India in 1947 as director of Fategarh Presbyterian Hospital where he led a medical team through the deadly riots of 1947 during the separation of India and Pakistan. In 1949, he conducted the first health survey of Nepal, then the most closed country in Asia. Back at Harvard, he completed his MPH and DrPH degrees. His doctoral dissertation provided the seminal research that defined the synergism between nutrition and infection, today a principle at the foundation of public health. In 1952, he founded the department of preventive medicine at the Christian Medical College Ludhiana, the first such department in the developing world.

Taylor was the founding chair of the Department of International Health at Johns Hopkins. He was instrumental in designing the global agenda for primary health care in the 1960s and 1970s. Before it was widely embraced, he was part of research and movements that connected women’s empowerment and holistic community-based change.

Throughout his life, Taylor had a particular interest in health care reform, especially the integration of services. His research achievements were wide-ranging. The Narangwal Rural Health Research Project in northern India, which he led from 1960 to 1975, provided breakthrough understandings in the diagnosis and treatment of childhood pneumonia, neonatal tetanus, getting medical care to the villages, synergism of malnutrition and child mortality, understanding childhood diarrheal treatment and community empowerment for just and lasting health solutions.

In addition to his 48 years at Johns Hopkins, Taylor was China Representative for UNICEF from 1984 to 1987. From 1992 until his death, he was senior advisor to Future Generations and more recently Future Generations Graduate School where a professorship is endowed in his name. From 2004 to 2006, he was Afghanistan Country Director for Future Generations, where he led field-based action groups using over 400 mosques as educational sites for Afghan women. He returned to Afghanistan in 2008 (at 92) to test hypotheses about how “women can in action groups solve the majority of their family health problems.”

Taylor was the primary World Health Organization consultant in preparing documents in 1978 for the Alma Ata World Conference on Primary Health Care. From 1957 through 1983, he advised WHO on a wide range of international health matters. In 1972, Taylor became the founding chair of the National Council for International Health, now known as the Global Health Council. He was also the founding chair of the International Health Section of the American Public Health Association.

Taylor published more than 190 peer-reviewed journal articles, books, chapters and policy monographs. In addition to his earned degrees, Taylor received honorary degrees from Muskingum College, Towson State University, China’s Tongji University, Peking Union Medical College and Johns Hopkins University. In 1993, President Bill Clinton recognized him for "Sustained work to protect children around the world in especially difficult circumstances and a life-time commitment to community based primary care.”

Taylor is survived by his two brothers, John and Gordon, two sisters, Gladys and Margaret, three children, Daniel, Betsy, Henry, and nine grandchildren. With an eight-decade long career in international health, he is beloved by thousands students and colleagues around the world. His stories of adventure and service enabled them to believe that they too could create just and lasting change. In the last year of his life, he was sitting with women in a bamboo hut in northeast India asking them how they would shape their futures, when they responded, “it is harra, the empowerment of ourselves.”

Persons wanting to send gifts may do so either to the Mary & Carl Taylor Fund, Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health (615 North Wolfe Street, Baltimore MD, 21205; www.jhsph.edu/giving.)

Carl Taylor: Bringing It All Together

Dr. Carl Taylor reflects on community health, the legendary 1978 Alma Ata conference on primary health care, and his students' opportunities to change public health. (3 minutes; from a 2008 interview.)

Additional information may be found at http://www.caringbridge.org/visit/carltaylor.

Donations can also be made to the Mary & Carl Fund for Global Mission, Brown Memorial Church, (www.browndowntown.org); or the Carl Taylor Scholarships, Future Generations Graduate School (Road Less Traveled, Franklin WV, 26807; www.future.org).