H1N1 Symposium: Getting the Facts

Click here to watch the symposium video

H1N1 vaccine trials have begun. Public health agencies have drafted emergency response plans. Hospitals are bracing for a spike in business.

As an expected second, more widespread wave of the H1N1 flu virus approaches this fall, public health systems around the world will be put to the test in ways not seen in decades.

At an H1N1 symposium at the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health on August 5, six experts on influenza, vaccine and public health policy outlined the emerging threats posed by the spread of H1N1 influenza—classified by the WHO as a pandemic earlier this summer—and addressed pharmaceutical and non-pharmaceutical interventions being studied and tested.

In a panel that followed, moderated by Jonathan Links, professor in Environmental Health Sciences, topics such as flu monitoring and vaccine policies were discussed in more depth.

A New Virus

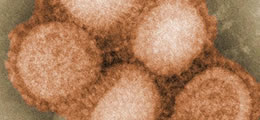

Waiting for the fall: H1N1 influenza A

This influenza A virus represents a unique gene constellation, one not seen before in humans, said Andrew Pekosz, associate professor in the W. Harry Feinstone Department of Molecular Microbiology and Immunology. “It’s a new virus,” he said, “with very little pre-existing immunity in the human population.” It thus presents a significant global threat.

At present, however, this virus is “nowhere near as virulent as the 1918 virus.” In fact, said Pekosz, PhD, the current H1N1 virus is only slightly more virulent than seasonal flu. But it seems to target different sets of people than the typical seasonal flus, which mostly affect the elderly: This virus targets pregnant women, children and adults 25 to 64 years of age.

Another cause for concern, according to Pekosz, is that the virus seems likely to form variants; a more virulent variant of H1N1 could profoundly affect the population. And because there is little pre-existing immunity to this virus, almost everyone will be susceptible to infection. (With seasonal flu, there is about 30 to 40 percent natural immunity in the population.)

Slowing Down Transmission

Derek Cummings, assistant professor in Epidemiology, stated that the WHO estimates that 35 to 40 percent of the world’s population will be infected with the H1N1 flu. Because there are still no good estimates on the case-fatality rate of the virus, Cummings pointed out, it is difficult to predict how serious the situation will become.

Cummings also discussed non-pharmaceutical interventions. “The goal,” said Cummings, PhD, MPH, “is to slow down transmission,” in an effort to limit the pressure on hospitals and to buy more time for vaccinations. So far, the best non-pharmaceutical interventions include use of masks and hand sanitizer—high adherence may reduce risk by up to 66 percent—and school closures.

Public health officials will continue to face difficult choices when it comes to striking a balance between containing H1N1 outbreaks and enacting measures that unnecessarily restrict society’s functioning. Last spring, some U.S. educators voiced concern that public health officials’ decision to close their schools was premature.

“With any kind of risk, what we care about is how frequently the bad thing happens, how severe it is when it does happen, and whether it is reversible,” said Nancy Kass, ScD, the Phoebe R. Berman Professor of Bioethics and Public Health. “We are much more likely as a society to step in with precautions if the consequences may be severe or irreversible. The key is to monitor data as they come in, and change response and policy if the approach we first took is not effective.”

Fast Track for Vaccine Production

Addressing the issue of vaccine production, Ruth Karron, professor in International Health, said that in her 30-year career this is the fastest testing track she’s seen. Because of the high demand for the vaccine, and the new sets of high-priority groups, the public health community will have to create categories and sub-categories of prioritization.

“Not enough doses will be available to immunize everyone all at once,” said Karron, MD. “We will have to immunize lots of kids very quickly.”

During the panel, Karron said that the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services has set a goal of having 600 million doses of the vaccine within six months of getting the seed virus, which became available in early July. But the virus intended for producing inactivated vaccines is growing less well than expected, a condition that will require dose-sparing initiatives. In addition, said Karron, “delivery will present incredible challenges.”

“Whether we can hit that goal depends how big a dose to use and whether we decide to use an adjuvant [an additive that improves a vaccine’s immune response] or not,” said Karron.

Also during the panel, Neal Halsey, director of the School’s Institute for Vaccine Safety and International Health professor, said that the Institute is actively working with the CDC to help monitor the safety of the H1N1 vaccines that will be used this fall. Guillain-Barre syndrome was identified in some people who received a swine flu vaccine in 1976, but the risk, if any, in subsequent years has been 1 per million or less. Given the threat posed by complications from H1N1, it’s an “easy decision to recommend you get the vaccine,” said Halsey.

“I think this is an incredibly important point in history for public health,” said Stephen Teret, associate dean for faculty and education, and professor in Health Policy and Management. “The world will be looking at whether public health gets this right or not, whether public health has credibility. The stakes are enormously high for public health that we get it right.” —Christine Grillo and Jackie Powder

H1N1: Getting the Facts: Symposium Video