The Public Health Approach to Prevent Gun Violence

A public health approach to prevent gun violence brings together a range of experts across sectors—including researchers, advocates, legislators, community-based organizations, and others—in a common effort to develop, evaluate, and implement equitable, evidence-based solutions.

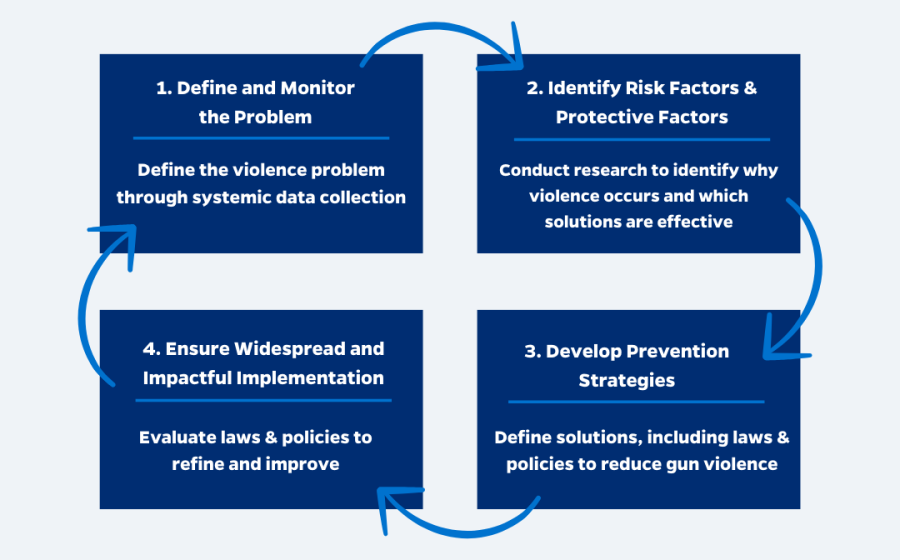

Public health is the science of reducing and preventing injury, disease, and death and promoting the health and well-being of populations through the use of data, research, and effective policies and practices. A public health approach to prevent gun violence is a population level approach that addresses both firearm access and the factors that contribute to and protect from gun violence. This approach brings together institutions and experts across disciplines in a common effort to: 1) define and monitor the problem, 2) identify risk and protective factors, 3) develop and test prevention strategies, and 4) ensure widespread adoption of effective strategies. By using a public health approach we can prevent gun violence in all its forms and strive towards health equity, where everyone can live free from gun violence.

Quick Facts About the Public Health Approach to Prevent Gun Violence:

Gun violence is a public health epidemic,

resulting in nearly 45,000 deaths annually in recent years (2019-2021) and an estimated 76,000 nonfatal injuries.1,2

The public health approach

addresses the many forms of gun violence by focusing both on firearm access and underlying risk factors that contribute to gun violence.

The public health approach is divided into four steps:

(1) define and monitor the problem,

(2) identify risk and protective factors,

(3) develop prevention strategies, and

(4) ensure widespread adoption of effective strategies.

The public health epidemic of gun violence is preventable.

We recommend evidence-based solutions to prevent gun death and injury in all of its forms. These solutions include, Firearm Purchaser Licensing, Extreme Risk Protection Orders and Domestic Violence Protection Orders, safe and secure gun storage, regulating the public carry of firearms, and Community Violence Intervention.

On This Page

Each day more than 120 Americans die by firearms.3 These deaths are preventable.

A comprehensive public health approach is needed to address the gun violence epidemic. This approach brings together a wide range of experts to determine the problem, identify key risk factors, develop evidence-based policies and programs, and ensure effective implementation and evaluation. Through a public health approach to gun violence, we can cure this epidemic, save thousands of lives, and make gun violence in America rare and abnormal.

What is Public Health?

Public health is the science of reducing and preventing injury, disease, and death and promoting the health and well-being of populations through the use of data, research, and effective policies and practices. Public health works to address the underlying causes of a disease or injury before they occur, promote healthy behaviors, and control the spread of outbreaks. Public health researchers and practitioners then work with communities and populations to implement and evaluate programs and policies that are based on research. Policymakers, researchers, and advocates have successfully used the public health approach in the United States to drastically decrease premature death rates, reduce injury, and improve the health and well-being of the population, including by eradicating diseases like polio, promoting widespread usage of vaccines, reducing smoking-related deaths, addressing environmental toxins, and decreasing motor vehicle crashes.

Why is Gun Violence a Public Health Epidemic?

Gun violence is a public health epidemic that affects the well-being and public safety of all Americans. In 2021, nearly 49,000 Americans were killed by gun violence, more than the number of Americans killed in car crashes.4 An additional 76,000 Americans suffer nonfatal firearm injuries, and millions of Americans face the trauma of losing a loved one or living in fear of being shot.5 The impacts of gun violence, both direct and indirect, inflict an enormous burden on American society. When a child is shot and killed, they lose decades of potential: the potential to grow up, have a family, contribute to society, and pursue their passions in life. When compared to other communicable and infectious diseases, gun violence often poses a larger burden on society in terms of potential years of life lost. In 2020, firearm deaths accounted for 1,131,105 years of potential life lost before the age of 65—more than diabetes, stroke, and liver disease combined.6

Scope of Gun Violence

Americans are impacted by various forms of gun violence – including suicide, homicide, and unintentional deaths, as well as nonfatal gunshot injuries, threats, and exposure to gun violence in communities and society.

Firearm Suicide:

-

Each year, nearly 25,000 Americans die by firearm suicide.7

-

Half of all suicide deaths are by firearm.8

-

Suicide attempts by firearm are almost always deadly — 9 out of 10 firearm suicide attempts result in death.9

-

Access to a firearm in the home increases the odds of suicide more than three-fold.10

Firearm Homicide:

-

Each year 18,000 Americans die by firearm homicide.11

-

Eight out of ten (79%) of homicides are committed with a firearm.12

-

Access to firearms — such as the presence of a gun in the home — doubles the risk for homicide victimization.13,14

-

The firearm homicide rate in the United States is 25.2 times higher than other industrialized countries.15

Domestic Violence:

-

More than half of female intimate partner homicides are committed with a gun.16

-

There are about 4.5 million women in America who have been threatened with a gun and nearly 1 million women who have been shot or shot at by an intimate partner.17

-

A woman is five times more likely to be murdered when her abuser has access to a gun.18

Police-Involved Shootings:

-

1,000 Americans are shot and killed by police every year.19

-

Black Americans are disproportionately impacted by police-involved shootings and are killed at more than twice the rate as White Americans.20

-

An estimated 800 of people are wounded by police shootings each year.21

Unintentional Shootings:

-

Each year, more than 520 people die from unintentional firearm injuries — an average of one death every 17 hours.22

-

More than 140 children and teens (0-19) die each year due to unintentional gun injuries.23

-

Americans are four times more likely to die from an unintentional gun injury than people living in other high-income countries.24

Mass Shootings:

-

Each year, there are an estimated 600 mass shootings with four or more people shot and/or killed in a single event — more than 500 people are killed and 2,000 are injured.25

-

From 2019 to 2021, there were an average of 27 incidents annually where four or more people were killed at a single event —in total more than 130 people were killed.26

-

From 2013 to 2022, the number of mass shootings (shootings where four or more people were shot and/or killed) have doubled; so too has the number of people killed and injured from the shootings.27

-

States with more permissive gun laws and greater gun ownership had higher rates of mass shootings.28

Nonfatal Firearm Injuries:

-

For every person in the United States who dies by firearm, two people are treated at hospitals for nonfatal gunshot wounds.29

-

Each year there are over 76,000 nonfatal gunshot injuries, costing hospitals an estimated $2.8 billion annually.30,31

-

Gun assaults and unintentional injuries make up the vast majority of nonfatal gun injuries; gun suicide attempts accounted for aproximetaly 5% of nonfatal gun injuries.32

Exposure to Gun Violence:

-

More than half of all adults in the U.S. report that they, or a family member have been involved in a gun violence-related incident.33

-

One in five adults say they have had a family member killed by a gun.

-

One in five adults report being personally threated or intimated with a gun.34

-

One-third of US adults report that fear of a mass shooting has prevented them from attending certain places or events.35

How Public Health Differs from Healthcare

People often assume that public health is the same as healthcare. While both strive to improve health and well-being, they approach this goal differently. In healthcare, the focus is on improving the health of the individual. In contrast, public health focuses on improving the health of an entire population through large-scale interventions and prevention programs.

Public health works to address the many factors that determine the health and well-being of populations. These factors are often referred to as risk and protective factors. They are characteristics or behaviors in individuals, families, communities, and the larger society that increase or decrease the likelihood of premature death, injury, or poor health.

What is the Public Health Approach?

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and World Health Organization outline a public health approach to violence prevention based on four steps: (1) define and monitor the problem, (2) identify risk and protective factors, (3) develop and test prevention strategies, (4) ensure widespread adoption of effective strategies.36,37

Step 1 - Define and monitor the problem

Researchers and policymakers need reliable data to understand the scope and complexity of gun violence. There are many different types of gun violence, and each type often requires different prevention strategies. Collecting and distributing reliable firearm data is essential to combating gun violence through a public health approach. Gun violence prevention researchers need reliable and timely data around the number of firearm fatalities and nonfatal injuries that occur in the United States each year. This data should include the demographics of the victim and shooter (if applicable), the location and time of the shooting, and the type of gun violence that occurred. Databases should classify the types of gun violence (suicides, intimate partner violence, mass shootings, interpersonal violence, police shootings, unintentional injuries) based on clearly defined and standardized definitions. This data should be made widely available and easily accessible to the general public free of charge.

Step 2 - Identify risk and protective factors

The public health approach focuses on prevention and addresses population level risk factors that lead to gun violence and protective factors that reduce gun violence. A thorough body of research has identified specific risk factors, both at the individual level and at the community and societal level, which increase the likelihood of engaging in gun violence. At an individual level, having access to guns is a risk factor for violence, increasing the likelihood that a dangerous situation will become fatal. Simply having a gun in one's home doubles the chance of dying by homicide and increases the likelihood of suicide death by over three-fold.38 Other individual risk factors closely linked to gun violence include: a history of violent behavior, exposure to violence, and risky alcohol and drug use.39,40 Community level factors also increase the likelihood of gun violence. Under-resourced neighborhoods with high concentrations of poverty, lack of economic opportunity, and social mobility are more likely to experience high rates of violence. These community level factors are often the result of deep structural inequities rooted in racism.41,42 Policies and programs should mitigate risk factors and promote protective factors at the individual and community levels.

Step 3 - Develop and test prevention strategies

Policymakers and practitioners must craft interventions which address the risk factors for gun violence. These interventions should be routinely tested to ensure they are effective and equitable; rigorous evaluations should be conducted on a routine basis. The foundation for effective gun violence prevention policy is a universal background check law, ensuring that each person who seeks to purchase or transfer a firearm undergoes a background check prior to purchase. Universal background checks should be supplemented by a firearm purchaser licensing system, which regulates and tracks the flow of firearms, to ensure that firearms do not make it into the hands of prohibited individuals. Building upon this, policymakers can create interventions which target behavioral risk-factors for gun violence (e.g. extreme risk laws, DVPO) and they can push for policies which address community risk factors that lead to violence (e.g. investing in community based violence prevention programs). In addition to these gun violence prevention policies, there are a number of evidence-based strategies that can reduce gun violence within communities. For example, community based violence intervention programs work to de-escalate conflicts, interrupt cycles of retaliatory violence, and support those at elevated risk for violence.

Step 4 - Ensure widespread adoption of effective strategies

While it is essential to pass strong laws, it is equally important to enforce and implement these laws and to scale up evidence-based programs. Strong gun violence prevention policies are only effective if they are properly implemented and enforced in an equitable manner. A key focus of the public health approach is ensuring that these strategies are not only effective but that they also promote equity. Historically disenfranchised groups should be involved in the implementation process to ensure that public health strategies do not have unintended consequences. For example, gun violence prevention policies should be consistently evaluated to ensure that they do not stigmatize individuals living with mental illness or perpetuate the discriminatory and racist practices embedded in the criminal justice system. The public health approach includes a focus on allocating funds for implementation and evaluation of these gun violence prevention strategies at the federal, state, and local level. Funds should be allocated to train the proper stakeholders to ensure that new policies and programs are properly adopted and achieve measurable and equitable outcomes.

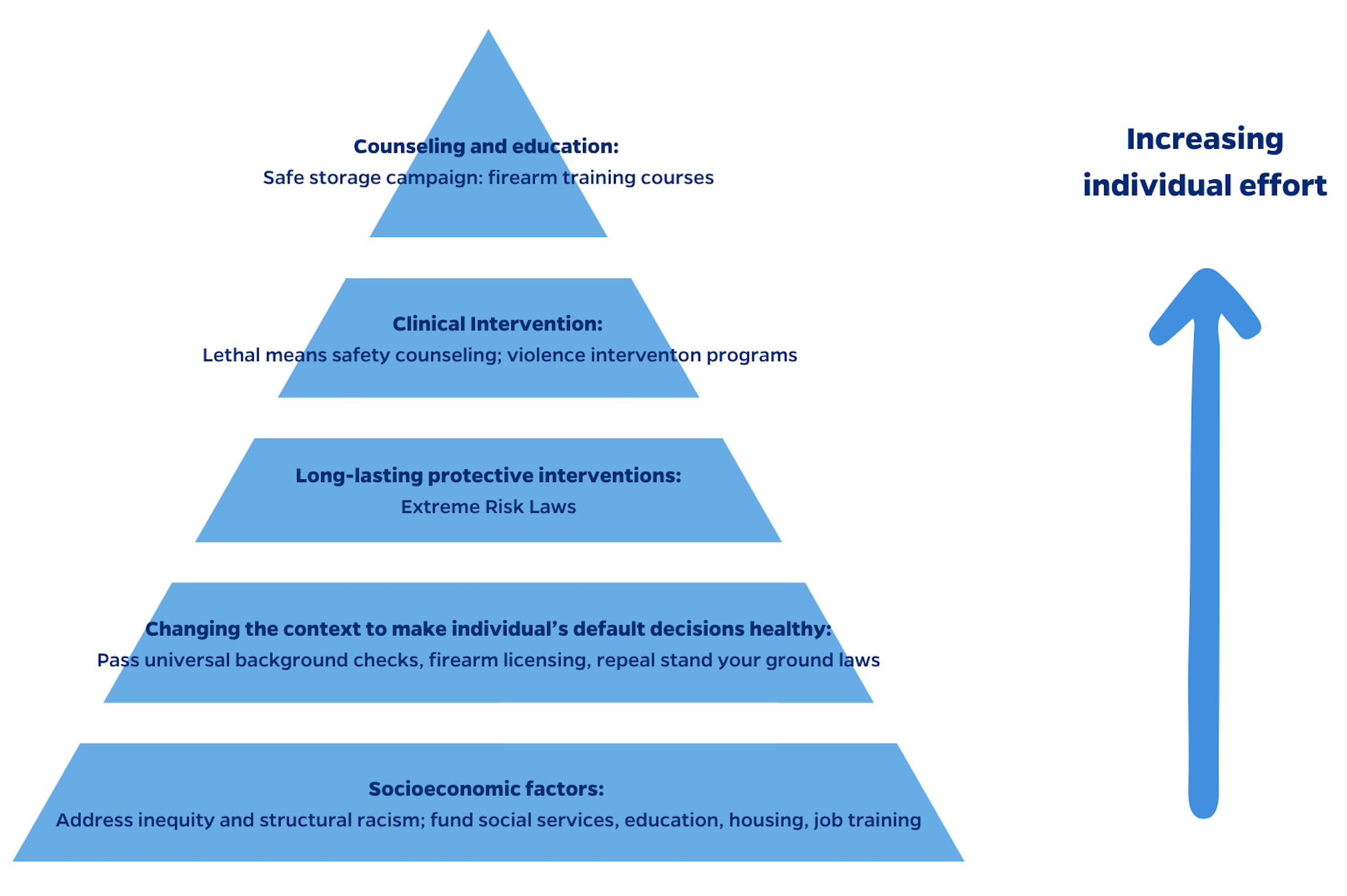

Health Impact Pyramid

The goal of public health is to maximize the overall health and well-being of populations. Public health practitioners do this by developing a wide-range of interventions. These interventions address risk and protective factors ranging from factors at the individual level to the societal level. The public health pyramid helps researchers conceptualize the many different levels of intervention needed to address a public health problem like gun violence.43

At the top of the pyramid are narrowly tailored interventions that work with individuals at risk for gun violence. These interventions, like lethal means safety counseling and violence intervention programs, can have tremendous impact in reducing gun violence. Yet, they also require individual action. These programs provide the tools and support to change behavior, but the individuals themselves must be willing to take action and change behavior.

The middle of the pyramid includes interventions that require less individual action. They are often laws and policies that change the environments within communities to mitigate risk factors. One such policy is universal background checks and firearm purchaser licensing. Research shows that when individuals are required to undergo a background check and obtain a license to purchase a firearm, far fewer firearms are diverted into illegal markets and used to perpetrate violence.

At the bottom of the public health pyramid are the conditions within society that lead to poor health outcomes like gun violence. These factors are often referred to as the root causes or social determinants of health. Socioeconomic factors, such as racial disparities, inequality, poverty, inadequate housing and education, are all risk factors for interpersonal gun violence. Policies that address these root causes have enormous potential to reduce gun violence and improve health. These policies, while requiring a broad collective effort to achieve, require minimal individual effort to be effective at reducing gun violence.

How Do We Address Gun Violence Through the Public Health Approach?

The public health approach is multifaceted and comprehensive and brings together institutions and experts across disciplines in a common effort to develop a variety of evidence-based interventions.45 This comprehensive approach to tackling public health crises in America has been used over the last century to eradicate diseases like polio, reduce smoking deaths, and make cars safer. This public health approach has saved millions of lives. We can learn from the public health successes -- like car safety -- and apply these lessons to preventing gun violence.

Applying the public health successes of car safety to prevent gun violence

One of the greatest American public health successes is our nation’s work to make cars safer.

By using a comprehensive public health approach to car safety, the United States reduced per-mile driving deaths by nearly 80% from 1967 to 2017.46 This public health approach to car safety prevented more than 3.5 million deaths over these fifty years.47 In the years since 2017 car crashes have begun to increase. This recent increase illustrates how threats to public health constantly evolve, and the work of public health practitioners is never complete. They must continue to monitor the problem, identify emerging risks, and develop new solutions. While the work in U.S. auto safety is far from complete, the comparisons illustrates the steps needed to address the epidemic of gun violence. To reduce gun violence, we should apply this same time-tested public health approach.

Sources: National Traffic Highway Safety Administration (NTHSA). Motor Vehicle Traffic Fatalities and Fatality Rates, 1899-2017; Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Health Statistics. National Vital Statistics System, Mortality 1968-2017 on CDC WONDER Online Database.

Applying the Public Health Successes of Auto Safety to Gun Violence Prevention

|

|

Preventing Car Crashes |

Preventing Gun Deaths |

|

Research |

Allocate funds to study the epidemic of motor vehicle crashes. |

Allocate funds to the CDC and the NIH to research gun violence. |

|

Regulate |

Federal agencies regulate car manufacturers and ensure car safety. |

Allow federal agencies to regulate firearm manufacturers and ensure gun safety. |

|

Licensing |

Drivers must submit an application and pass a test to obtain a driver’s license. |

Require firearm purchasers to submit an application, undergo a background check, and take safety education to obtain a license to own a firearm. |

|

Registration |

Car registration is required at each point of sale. |

Pass firearm registration laws to ensure that firearms are registered at each point of sale. |

|

Prohibit Risky People |

Reckless and drunk driving laws ensure that risky individuals do not endanger others on the road. |

Expand firearm prohibitions to include individuals who are at elevated risk for violence. |

|

Manufacturing Standards |

Manufacturers are required to make safer cars by installing seat belts and airbags. |

Require manufacturers to make fireams safer, including requiring that guns be outfitted with microstamping technology. |

|

Age Requirements |

Age requirements for obtaining a driver’s license, including a graduated licensing system (driver’s permit) for young drivers. |

Enact stronger age requirements for owning or possessing all types of firearms. |

|

Licensing Renewal |

Drivers are required to renew their license periodically. |

Require gun owners to renew their license on a routine basis. |

|

Ongoing Monitoring and Regulation |

New models of cars are monitored and regulated, and recalls are issued for unsafe models. |

Allow Consumer Product Safety Commission to regulate safety of firearms and ensure industry accountability. |

|

Liability |

Manufacturers are held liable if they sell a dangerous vehicle. |

Repeal the Protection of Lawful Commerce in Arms Act (PLCAA) to hold firearm manufacturers accountable for dangerous and reckless distribution of firearms. |

Recommendations

Apply the public health approach for effective gun violence prevention.

Public health is the science of reducing and preventing injury, disease, and death and promoting the health and well-being of populations through the use of data, research, and effective policies and practices. The public health approach has been successfully applied to tackle a wide variety of complex health problems at the population level. Gun violence is a public health epidemic that requires a public health solution. We recommend the following:

Better Data Collection

Federal, state, and local governments should collect more comprehensive gun violence data for fatal and non-fatal firearm injuries, shootings that may not involve physical injuries, and firearm-involved crimes where no shots were fired, including domestic violence-related threats. Federal, state, and local governments should make data publicly available where possible and particularly to researchers studying gun violence and its prevention.

Research Funding

Enhanced research funding is key for advancing knowledge and improving public health interventions and outcomes. Federal, state, and local governments, in addition to foundations and universities, should dedicate funding to research gun violence prevention.

Evidence-based Policies and Practices

Gun violence is a muliticated problem that takes many forms and requires a multitude of data-driven solutions. Gun violence prevention policies and practices should be evidence-based.

- Firearm Purchaser Licensing or permit-to-purchase laws require all prospective gun purchasers to obtain license prior to buying a gun from a dealer or a private seller. These laws enhance universal background checks by establishing a licensing application process as well as considering additional components such as fingerpinting, a more through vetting process, and a built-in waiting period to prevent individuals with a history of violence, those at risk for future interpersonal violence or suicide, and gun traffickers from obtaining firearms.

- Extreme Risk Protection Order (ERPO) is a civil process allowing law enforcement, family members, and, in some states, medical professionals and other parties to petition a court to temporarily restrict access to guns from individuals determined to be at elevated risk of harming themselves or others. ERPO laws are associated with lower rates of firearm suicide and have been successfully used in mass shooting threats.48

- Community Violence Intervention (CVI) programs aim to identify and support the small number of people at risk for violence by providing them with wraparound mental health and social supports. Investing in CVI programs provides a public health approach to gun violence prevention, interrupting cycles of violence, and addressing the unique needs of the community where systemic racism, disinvestment, and trauma occur.

- Safe and secure gun storage practices, such as Child Access Prevention (CAP) laws, require households with a child or teen to keep firearms unloaded and locked when unattended. These practices promote responsible firearm storage practices protecting children and teenagers from various forms of gun violence, including unintentional shootings and gun suicides. CAP laws are linked to sizable reductions in child and teen gun deaths, including reductions in youth suicide, accidental shootings, and homicides.49,50

- Public carry of firearms poses a serious threat to safety. Permissive public carry and “stand your ground” laws increase violence by allowing people with violent histories to carry their firearms in public, providing more opportunities for armed intimidation and shootings in response to hostile interactions, and increasing criminals’ access to guns. States should regulate the carrying of guns in public by prohibiting open carry of firearms particularly in sensitive places, passing strong concealed carry permitting laws, and repealing “stand your ground” laws.

Implementation and Evaluation

It is essential to pass evidence-based policies that address gun violence, but that is not enough. Gun violence takes many forms and impacts a variety of groups, requiring ongoing surveillance and evaluation to ensure effective implementation of policies and practices. Federal, state, and local governments should dedicate resources to ensure proper implementation, education and ongoing evaluation of gun violence prevention policies.

Citations

1 Three-year average, 2019-2021. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Health Statistics. Underlying Cause of Death. Available: https://wonder.cdc.gov/ucd-icd10-expanded.html.

2 Song Z, Zubizarreta JR, & Giuriato M. (2022). Changes in health care spending, use, and clinical outcomes after nonfatal firearm injuries among survivors and family members. Annals of Internal Medicine. https://doi.org/10.7326/M21-2812

3 Three-year average, 2019-2021. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Health Statistics. Underlying Cause of Death. Available: https://wonder.cdc.gov/ucd-icd10-expanded.html.

4 Three-year average, 2019-2021. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Health Statistics. Underlying Cause of Death. Available: https://wonder.cdc.gov/ucd-icd10-expanded.html.

5 Schnippel K, Burd-Sharps S, Miller T, Lawrence B, Swedler DL. (2021). Nonfatal firearm injuries by intent in the United States: 2016-2018 Hospital Discharge Records from the Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project. Western Journal of Emergency Medicine: Integrating Emergency Care with Population Health. https://doi.org/10.5811/westjem.2021.3.51925

6 National Center for Injury Prevention and Control, CDC. WISQARS Years of Potential Life Lost (YPLL) Report. Available: https://www.cdc.gov/injury/wisqars/index.html

7 Three-year average, 2019-2021. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Health Statistics. Underlying Cause of Death. Available: https://wonder.cdc.gov/ucd-icd10-expanded.html.

8 Three-year average, 2019-2021. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Health Statistics. Underlying Cause of Death. Available: https://wonder.cdc.gov/ucd-icd10-expanded.html.

9 Conner A, Azrael D, & Miller M. (2019). Suicide case-fatality rates in the United States, 2007 to 2014: A nationwide population-based study. Annals of Internal Medicine.

10 Anglemyer A, Horvath T, & Rutherford G. (2014). The accessibility of firearms and risk for suicide and homicide victimization among household members: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Annals of Internal Medicine.

11 Three-year average, 2019-2021. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Health Statistics. Underlying Cause of Death. Available: https://wonder.cdc.gov/ucd-icd10-expanded.html.

12 Three-year average, 2019-2021. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Health Statistics. Underlying Cause of Death. Available: https://wonder.cdc.gov/ucd-icd10-expanded.html.

13 Anglemyer A, Horvath T, & Rutherford G. (2014). The accessibility of firearms and risk for suicide and homicide victimization among household members: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Annals of Internal Medicine.

14 Dahlberg LL, Ikeda RM, & Kresnow MJ. (2004). Guns in the home and risk of a violent death in the home: findings from a national study. American Journal of Epidemiology.

15 Choron R, Spitzer S, & Sakran JV. (2019). Firearm violence in America: is there a solution? Advances in Surgery.

16 Zeoli AM, Malinski R, & Turchan B. (2016). Risks and targeted interventions: Firearms in intimate partner violence. Epidemiologic Reviews.

17 Sorenson SB, & Schut RA. (2018). Nonfatal Gun Use in Intimate Partner Violence: A Systematic Review of the Literature. Trauma, Violence, & Abuse.

18 Campbell JC, Webster D, Koziol-McLain J, Block C, Campbell D, Curry MA… & Laughon K. (2003). Risk factors for femicide in abusive relationships: results from a multisite case control study. American Journal of Public Health.

19 Fatal Force database. (2020). Washington Post.

20 Fatal Force database. (2020). Washington Post.

21 Average annual nonfatal shootings by police, 2018-2020. Ward, J. A. (2023). Beyond Urban Fatalities: An Analysis of Shootings by Police in the United States (Doctoral dissertation, Johns Hopkins University).

22 Three-year average, 2019-2021. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Health Statistics. Underlying Cause of Death. Available: https://wonder.cdc.gov/ucd-icd10-expanded.html.

23 Three-year average, 2019-2021. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Health Statistics. Underlying Cause of Death. Available: https://wonder.cdc.gov/ucd-icd10-expanded.html.

24 Solnick SJ, & Hemenway D. (2019). Unintentional firearm deaths in the United States 2005–2015. Injury Epidemiology.

25 Three-year average, 2019-2021. Gun Violence Archive. (2023). Available: https://www.gunviolencearchive.org/.

26 Three-year average, 2019-2021. Gun Violence Archive. (2023). Available: https://www.gunviolencearchive.org/.

27 Gun Violence Archive. (2023). Available: https://www.gunviolencearchive.org/.

28 Reeping PM, Cerda M, Kalesan B, Wiebe DJ, Galea S, & Branas CC. (2019). State gun laws, gun ownership, and mass shootings in the US: Cross sectional time series. BMJ Journal. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.l542

29 Schnippel K, Burd-Sharps S, Miller T, Lawrence B, Swedler DL. (2021). Nonfatal firearm injuries by intent in the United States: 2016-2018 Hospital Discharge Records from the Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project. Western Journal of Emergency Medicine: Integrating Emergency Care with Population Health. https://doi.org/10.5811/westjem.2021.3.51925

30 Schnippel K, Burd-Sharps S, Miller T, Lawrence B, Swedler DL. (2021). Nonfatal firearm injuries by intent in the United States: 2016-2018 Hospital Discharge Records from the Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project. Western Journal of Emergency Medicine: Integrating Emergency Care with Population Health. https://doi.org/10.5811/westjem.2021.3.51925

31 Avraham JB, Frangos SG, & DiMaggio CJ. (2018). The epidemiology of firearm injuries managed in US emergency departments. Injury Epidemiology.

32 Schnippel K, Burd-Sharps S, Miller T, Lawrence B, Swedler DL. (2021). Nonfatal firearm injuries by intent in the United States: 2016-2018 Hospital Discharge Records from the Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project. Western Journal of Emergency Medicine: Integrating Emergency Care with Population Health. https://doi.org/10.5811/westjem.2021.3.51925

33 One in Five Adults Say They’ve Had a Family Member Killed by a Gun, Including Suicide, and One in Six Have Witnessed a Shooting; Among Black Adults, a Third Have Experienced Each. (2023). KFF. Available: https://www.kff.org/other/press-release/one-in-five-adults-say-theyve-had-a-family-member-killed-by-a-gun-including-suicide-and-one-in-six-have-witnessed-a-shooting-among-black-adults-a-third-have-experienced-each/

34 One in Five Adults Say They’ve Had a Family Member Killed by a Gun, Including Suicide, and One in Six Have Witnessed a Shooting; Among Black Adults, a Third Have Experienced Each. (2023). KFF. Available: https://www.kff.org/other/press-release/one-in-five-adults-say-theyve-had-a-family-member-killed-by-a-gun-including-suicide-and-one-in-six-have-witnessed-a-shooting-among-black-adults-a-third-have-experienced-each/

35 One-third of US Adults say fear of mass shootings prevents them from going to certain places or events. (2019) American Psychological Association. Press Release. https://www.apa.org/news/press/releases/2019/08/fear-mass-shooting

36 Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. The National Center for Injury Prevention and Control, Division of Violence Prevention. The Public Health Approach to Violence Prevention.

37 World Health Organization. Violence Prevention Alliance. The Public Health Approach.

38 Anglemyer A, Horvath T, & Rutherford G. (2014). The accessibility of firearms and risk for suicide and homicide victimization among household members: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Annals of Internal Medicine.

39 Consortium for Risk‐Based Firearm Policy. (2013). Guns, public health, and mental illness: An evidence-based approach for state policy.

40 Consortium for Risk‐Based Firearm Policy. (2023). Alcohol Misuse and Gun Violence: An Evidence-Based Approach for State Policy. Available: https://riskbasedfirearmpolicy.org/reports/alcohol-misuse-and-gun-violence-an-evidence-based-approach-for-state-policy/

41 Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2019). Risk and Protective Factors.

42 Sampson RJ. (2012). Great American city: Chicago and the enduring neighborhood effect. University of Chicago Press.

43 Frieden TR. (2010). A framework for public health action: the health impact pyramid. American journal of public health.

44 Frieden, TR. (2010). A framework for public health action: The health impact pyramid. American Journal of Public Health. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2009.185652

45 Hemenway D, & Miller M. (2013). Public health approach to the prevention of gun violence. New England Journal of Medicine.

46 Traffic Safety Facts: A Compilation of Motor Vehicle Crash Data. (2020). Annual Report Tables. National Highway Traffic Safety Administration. Available:

47 On 50th anniversary of ralph nader’s ‘unsafe at any speed,’ safety group reports auto safety regulation has saved 3.5 million lives. (2015). The Nation.

48 Research on Extreme Risk Protection Orders: An Evidence-Based Policy That Saves Lives. (2023). Johns Hopkins Center for Gun Violence Solutions. Available: https://publichealth.jhu.edu/sites/default/files/2023-02/research-on-extreme-risk-protection-orders.pdf

49 Azad HA, Monuteaux MC, Rees CA, Siegel M, Mannix R, Lee LK, Sheehan KM, & Fleegler EW. (2020). Child Access Prevention firearm laws and firearm fatalities among children aged 0 to 14 Years, 1991-2016. JAMA Pediatrics. https://jamanetwork.com/journals/jamapediatrics/fullarticle/2761305

50 Webster DW, Vernick JS, Zeoli AM, & Manganello JA. (2004). Association between youth-focused firearm laws and youth suicides. Jama Network. https://jamanetwork.com/journals/jama/fullarticle/199194