Community Gun Violence

What is Community Gun Violence?

Community gun violence is a form of interpersonal gun violence (assaults) that takes place between individuals who are not related or in an intimate relationship. It typically occurs in public places — streets, parks, front porches — in communities across America, and it makes up most gun homicides that occur in the United States.1 Most community gun violence is highly concentrated within under-resourced neighborhoods impacted by a legacy of discriminatory public policies.2,3 Consequently, Black and Hispanic/Latino Americans are disproportionately impacted by community gun violence.

Community gun violence is a form of interpersonal gun violence that:

Takes Place in Under-Resourced Neighborhoods

and affects disinvested communities

Disproportionately impacts Black and Hispanic/Latino communities

specifically young Black and Hispanic/Latino men

Usually occurs outside of the home in a public setting

Excludes domestic and intimate partner violence

Often is sparked by a dispute between individuals or groups

and may be retaliatory because of long-standing conflicts

Who is Impacted by Community Violence?

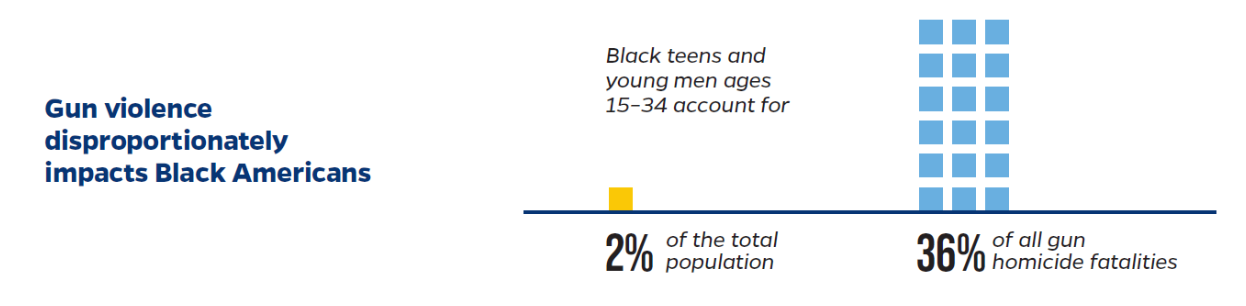

Black Americans were nearly 14 times as likely to be murdered by firearm as their white counterparts in 2021. Young Black males ages 15-34 made up 2% of the U.S. population but account for 36% of all firearm homicide fatalities that year. Gun violence is the leading cause of death for Black males ages 15-34.4

In 2021, gun violence was the second leading cause of death for Hispanic/Latino males under the age of 34, and Hispanic/Latino males ages 15-34 are 3.4 times more likely to be murdered by firearm than their White (non-Hispanic/Latino) counterparts.5

Firearm Homicide Rates by Disproportionately Impacted Populations, 2019-2021 (rates per 100,000 people)

| National rate | Male | Black male | Black males living ages 15-34 |

|---|---|---|---|

| 5.53 | 9.45 | 48.91 | 107.31 |

Difference in Gun Homicide Rates by Gender and Race/Ethnicity, 2022

Source: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Health Statistics. Underlying Cause of Death. Gun Deaths and Rates per 100,000. WONDER Online Database, 1999-2022.

*The total number of gun homicide deaths for female Native Hawaiian or Other Pacific Islander were less than 10 and thus repressed by CDC.

Where does Community Gun Violence Occur?

Community gun violence is geographically concentrated in a small number of under-resourced neighborhoods composed of predominantly Black and Hispanic/Latino residents. For example, an analysis of firearm homicide data from 2015 found that 26% of all firearm homicides in the United States occurred in census tracts that contained only 1.5% of the American population.6

These neighborhoods suffer from underfunded social services, few economic opportunities, and concentrated poverty.7

Often public attention focuses on cities with high homicide rates, with little attention given to where, within the city, violence occurs and which communities bear the brunt of it. St. Louis, a city that frequently tops the charts in terms of homicides, illustrates how gun violence is geographically concentrated. An analysis of 2015 data found that 42% of the city’s homicides occurred in just 8 out of the city’s 79 residential neighborhoods.8 Among the homicides that year, nine people were murdered by firearms in nine separate shootings, all within one 0.4 square mile census tract.9

Community gun violence is not just confined to cities. In fact, many rural communities are also impacted by gun violence. Ten of the 20 counties with the highest gun homicide rates from 2019 to 2021 were rural.10 Out of 3,142 counties, Lowndes County, Alabama, with only 10,000 residents, had the country’s highest homicide rate from 2019 to 2021. Meanwhile, Cook County (Chicago), which often captures the media’s attention around violence, had the 61st highest gun homicide rate. To adequately address the crisis of community gun violence policymakers must understand its uneven distribution, and the populations, both in rural and urban America, that are most impacted.

"To reduce community gun violence, strategies must be informed by detailed data on the drivers and circumstances surrounding shootings and involve strategic partnerships between government agencies and community-based organizations who can effectively engage with those at highest risk and counteract the drivers of gun violence."

Daniel Webster, ScD '91, MPH

Distinguished Research Scholar, Johns Hopkins Center for Gun Violence Solutions

Small Social Networks

Even within the neighborhoods with the highest levels of violence, only a few individuals are involved in gun violence, and those involved are often both the perpetrator and victim.11,12,13 Analyses in a variety of cities have found that small networks of individuals -- sometimes as little as a couple hundred in a city of millions -- are involved in most of the city’s shootings. In Oakland, for instance, just 0.1% of the population were responsible for the majority of the city’s homicides,14 while in New Orleans, networks of 600 to 700 individuals are linked to most of the city’s murders.15 Even within Chicago’s highest violence neighborhoods, those who have a social network in which someone was murdered are 900% more likely to die of homicide than neighboring residents.16 The vast majority of homicides in each of these cities are by firearms.

Community gun violence can be reduced through narrowly tailored interventions which focus on the small number of individuals caught in cycles of violence.

What Factors Influence Community Gun Violence?

Social and economic inequalities are often at the root of community gun violence. These inequalities are caused by racist policies like redlining and exclusionary zoning laws that target communities of color and create segregated and underinvested neighborhoods.17 The same neighborhoods struggling with community gun violence also face multiple economic challenges including the lack of access to healthy food, shortage of affordable housing, high rates of environmental lead exposure, inadequate education, few jobs, and limited opportunities.18,19

Within many neighborhoods with high rates of violence, the unemployment rate is over 20%.20 The typical household within a high poverty neighborhood has a net worth of $7,000 -- 1/40th of the typical household in a low poverty neighborhood.21 Likewise, there is often a lack of educational opportunities, as the schools are chronically underfunded.22 Over a quarter of adults living in high poverty neighborhoods lack a high school diploma and only 14% have attained a bachelor's degree.23 These deep structural disadvantages combined with easy access to guns create the conditions for community gun violence.

Conditions that increase the likelihood of community gun violence include:

→ Easy access to guns by people at elevated risk for violence24

→ Income inequality25

→ Concentrated poverty26

→ Underfunded public housing27

→ Under-resourced public services28

→ Underperforming schools29

→ Lack of opportunity and perceptions of hopelessness30

→ Police brutality and lack of police legitimacy31

How Policing Practices Impact Community Gun Violence

Policing, if applied correctly, can serve as an important role in effectively addressing community gun violence. Policing gun violence requires strategic use of police resources focused on the people, places and behaviors that contribute to violence. Research shows that properly implemented policing strategies including, hot spots policing, focused deterrence, and enhanced shooting investigations can reduce community gun violence, and strengthen trust with the community.32

Hot Spots Policing:

Police should focus patrol activities to locations identified as “hot spots” for gun violence, driven by real-time data of shootings. These enforcement strategies must be conducted in a lawful, procedurally just manner to prevent harms and promote police legitimacy. Police can also allocate resources to high-risk places and address underlying problems, like poor lighting, which contribute to violence. Hot spot policing strategies are associated with reductions in violent crime and disorder.33

Group Violence Intervention:

Police should partner with community-based organizations and social service agencies to create a focused deterrence, or group violence intervention model. This model aims on changing the behavior of the small groups of people involved in gun violence. Individuals are offered opportunities and resources to change their behavior. Law enforcement dedicate resources toward apprehending those that continue to engage in gun violence. This strategy works best when there is a balance between law enforcement deterrents and supports from community-based organizations.34

Enhanced Shooting Investigations:

Unsolved shootings contribute to gun violence by depriving victims and their families of justice and exacerbating police-community relations. In many jurisdictions only a fraction of gun crimes are solved. Homicides and shootings of Black people, or that occur in under-resourced neighborhoods, are solved at far lower rates than homicides and shootings of white people or that occur in wealthier neighborhoods.35,36 Police should prioritize fatal and nonfatal shooting investigations, particularly those that occur in under-resourced neighborhoods, to address low clearance rates and interrupt the cycle of gun violence. When police departments increase resources and personnel to investigate shootings (both fatal and nonfatal), they can solve more shootings.37

Building Police Legitimacy is Essential to Reducing Community Gun Violence

Police legitimacy is the way community members trust in, and are willing to work with, the police. It is a vital component in reducing community gun violence. When communities view the police force as legitimate, they are more willing to work with law enforcement to identify and detain those responsible for committing acts of gun violence, and to intervene before conflicts develop into shootings. Likewise, when police legitimacy is strong, victims of violence feel safe and can rely on formal channels of justice to bring about closure, instead of resorting to retaliation.38

Police brutality and widespread discrimination undermine police legitimacy, and thereby fuel community gun violence. In many Black and Hispanic communities distrust in law enforcement stems from a legacy of racist policies and violence, often carried out by police. Compounded upon this history is the ongoing crisis of mass incarceration and police brutality.39 Research consistently highlights racial disparities at virtually every step within the criminal justice system. Black males are stopped by police, arrested, denied bail, wrongfully convicted, issued longer sentences, and shot by police at much higher rates than white Americans.40

Unsurprisingly, when individuals experience police discrimination or brutality, they are less likely to trust or rely on law enforcement. Consequently, these community members are reticent to report criminal activity or act as witnesses in criminal investigations. Instead, some rely on informal channels of justice – like retaliatory violence – to resolve conflict.41

A 2016 study examined the relationships between police brutality, police legitimacy, and homicide rates in Milwaukee, Wisconsin. The authors examined the highly publicized, brutal beating of an unarmed Black man, Frank Jude, by Milwaukee police officers in 2004. The authors found that in the year after the beating, calls for police services dropped dramatically in the city, particularly in underserved minoritized neighborhoods. In the year following the beating there were 22,200 fewer 911 calls. This decrease in 911 calls coincided with a spike in homicides. In the six months following this beating, homicides in Milwaukee increased by 32%.42 The authors conclude that this one act of police brutality eroded trust in law enforcement and likely contributed to increases in gun violence. This study illustrates how police brutality is both unconscionable in its own right and may fuel community gun violence.

Police departments should build an organizational culture to address police misconduct and discrimination through internal policy changes, including hiring, training, use of force, and accountability practices.

Gun Homicide Rate by Race and Age, 2022

Source: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Health Statistics. Underlying Cause of Death. Gun Deaths and Rates per 100,000. WONDER Online Database, 1999-2022.

How can Community Gun Violence be Prevented?

Reduce the flow of illegal guns into impacted communities.

Stemming the flow of illegal guns into Black and Hispanic/Latino communities is vital to reducing community gun violence. There are no federally licensed firearms dealers in many communities most impacted by gun violence, yet there is often an abundance of firearms. Gun violence prevention policies that address firearm trafficking and prevent dangerous people from accessing firearms play an important role in reducing community gun violence. These laws include firearm purchaser licensing laws with universal background checks and lost and stolen firearm reporting laws.

Lost and stolen firearm reporting laws:

Each year an estimated 380,000 firearms are stolen in the U.S yet only 240,000 are reported to law enforcement.43,44 This suggests that an estimated 140,000 gun thefts are not reported to law enforcement each year. Laws that require gun owners to promptly report lost or stolen firearms to law enforcement can help prevent firearm trafficking. These laws both increase gun seller accountability and provide police with a tool to combat firearm traffickers. States that have lost and stolen firearm reporting laws were associated with 30% lower rates of crime gun exports to other states compared to states without such laws.45

Firearm Purchaser Licensing:

Firearm purchaser licensing laws, also known as permit-to-purchase, require an individual to qualify for and obtain a license before acquiring or owning a firearm. Individuals generally must fill out an in-person application at the police department, be fingerprinted, and undergo a comprehensive criminal background check. Firearm purchaser licensing laws are found to be effective at deterring individuals who commit violent crimes and gun traffickers from obtaining firearms. For example, the repeal of Missouri’s licensing law was associated with the increased diversion of guns into the illegal market.46 Research also shows that licensing laws are an effective policy to prevent firearm homicides. Licensing laws are associated with an 11% reduction in firearm homicides in urban counties.47

Gun Dealer Oversight and Litigation:

In 2022, Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, Firearms and Explosives was only able to inspect approximately nine percent of the 78,000 licensed gun dealers in the United States as a result of insufficient resources and legal restrictions.48 Federal immunity laws, including the Protection of Lawful Commerce in Arms Act (PLACA), and additional exemptions from 34 states provide additional protections for gun manufacturers, dealers, and other industry-related members from liability and accountability in court.49 Comprehensive gun dealer reforms, including strong gun dealer regulations and oversight, should be prioritized to hold gun dealers accountable when they break the law. Additionally, states can pass legislation to hold the gun industry accountable for reckless marketing practices. They can expand the ability of victims and/or public officials to bring lawsuits to civil court against the gun industry manufacturers for misconduct.

Deploy policing strategies that are highly focused and that increase trust within communities most impacted by gun violence

Law enforcement play an essential role in curbing community gun violence by enforcing gun laws and detaining those who commit gun crimes. Police department should deploy strategies that are highly focused on the small number of individuals involved in gun violence, the areas where gun violence concentrates and the criminal behaviors that contribute to violence. Evidence consistently shows that a range of these policing strategies can reduce levels of gun violence. 50

For police departments to maintain sustained reductions in violence they need to be viewed as legitimate institutions in the communities most impacted by violence. Policymakers and police departments must work to improve relationships between law enforcement and the communities they serve. To do this, police departments should adopt procedurally just practices. Procedural justice requires a long-term commitment from law enforcement leaders to institute a culture in which police see the community as partners and respond to the expressed needs of the community. In order for these partnerships to take root there must be a law enforcement culture of transparency and citizen oversight. Community members should feel they have a voice in the decision-making process and decisions should be made in a fair and neutral way.51,52 For procedurally just practices to work, police must also be effective in curbing violence.

Community violence intervention and prevention programs

Community violence intervention and prevention efforts work with those impacted by gun violence to reduce the cycles of community gun violence, address the underlying causes of gun violence, and promote health equity. Community violence intervention and prevention programs bring together community members, social service providers, and, in some cases, law enforcement to identify and provide support for individuals at highest risk for gun violence. They also help individuals cope with the trauma that is associated with living in neighborhoods where witnessing gun violence is routine.

Violence Reduction Councils (VRC)

An interdisciplinary, data-driven and public health-focused approach to violence prevention and intervention.

VRCs create a framework for community members from diverse backgrounds to collaborate and identify recommendations proven to: prevent violence, meet the unique needs of the community, and rebuild trust among local governments, law enforcement and community members

VISIT THE VRC WEBSITE READ THE TOOLKIT

EFFECTIVE VIOLENCE INTERVENTION AND PREVENTION PROGRAMS

Street outreach and violence interruption programs

In the street outreach and violence interruption model, outreach workers are trained to identify conflicts within their community and help resolve disputes before they spiral into gun violence. These outreach workers are credible members of the community and well-respected by individuals at a high risk of violence. Outreach workers use their credibility to interrupt cycles of retaliatory violence, help connect high risk individuals to social services, and change norms around using guns to solve conflicts.

Evidence:

Violence interruption programs, like the Cure Violence model, have been used successfully in multiple cities, including Chicago, Philadelphia, and New York. An evaluation of Baltimore’s Cure Violence program found that it was associated with a 22% reduction in homicides and 23% reduction in nonfatal shootings from 2007 to 2021.53, 54

Group Violence Intervention / Focused Deterrence

In the Group Violence Intervention / Focused Deterrence model, prosecutors and police work with community leaders to identify a small group of individuals who are chronic violent offenders and are at high risk for future violence. High risk individuals are called into a meeting and are told that if violence continues, every legal tool available will be used to ensure they face swift and certain consequences. These individuals are simultaneously connected to social services and community support to assist them in changing their behavior.

Evidence:

An analysis of 24 focused deterrence programs found that these strategies led to an overall statistically significant reduction in firearm violence. The most successful of these programs have reduced violent crime in cities by an average of 30% and improved relations between law enforcement officers and the neighborhoods they serve.55

Trauma-informed Programs with Cognitive Behavioral Therapy

Trauma-informed programs that employ cognitive behavioral therapy to those at risk for violence have experienced significant decreases in firearm violence.56 Cognitive behavioral therapy helps high risk individuals cope with trauma while simultaneously providing new tools to de-escalate conflict.

Evidence:

Trauma-informed programs in Chicago that provide high risk youth with cognitive behavioral therapy and mentoring cut violent crime arrests in half.57

Violence Reduction Councils / Homicide Review Commissions

Violence reduction Councils (also known as homicide review commissions) bring together law enforcement, public health agencies, community members, criminal justice stakeholders, and service providers to examine firearm violence within their community. Stakeholders collaboratively develop comprehensive interventions that identify high risk individuals and address the underlying factors that lead to violence.

Evidence:

The homicide review commission in Milwaukee was associated with a significant and sustained 52% reduction in homicides.58 A Department of Justice evaluation found homicide review commissions to be an effective way to reduce gun violence by building trust between criminal justice stakeholders and the community.59

Programs that clean and rehabilitate blighted and abandoned property

These programs prevent gun violence by reducing the locations where illegal guns are stored and often where illegal activity linked to gun violence occurs. Likewise, these programs increase the connectedness between neighbors and strengthen the informal social controls that deter violence.

Evidence:

An evaluation of a blight remediation program in Philadelphia found that it was associated with a decrease in gun violence by 39% over one year and improved community health.60

Comprehensive Investments in Violence Intervention and Prevention Programs

When properly funded and implemented, community violence intervention and prevention efforts reduce gun violence. Federal, state, and local governments have the ability to support violence intervention and prevention efforts by providing funding, staffing, technical assistance and capacity building.

City level efforts to address community gun violence:

Cities can support community violence intervention programs by making them an integral part of city government, like any other city service. Many cities have created offices of violence prevention and intervention (often also called offices of neighborhood safety) to build, fund, and coordinate community violence intervention and prevention efforts across the city.

These agencies, often housed in a public health department or within the mayor’s office, can lead a public health-based approach to violence prevention by convening city agencies, services providers, and community-based organizations involved in violence prevention. They can do this through creating a framework like the Violence Reduction Council, in which key stakeholders in the city work together to identify the risk and protective factors within a city and develop interventions informed by data.

Oakland, California provides an excellent example of how investing in CVI, in partnership with law enforcement, can promote reforms in policing and reduce violence. Oakland adopted a special tax that provides significant and consistent funding for CVI programs. In 2012, the city implemented Ceasefire, a program that conducts in-depth problem analysis to identify individuals and groups involved in gun violence and engage these individuals with a clear message from law enforcement and the community that the violence must stop. Significant outreach and social support were offered in addition to a deterrence message. Additionally, the city invested in violence interruption and hospital-based violence intervention programs to provide a wide-range of support to those at highest risk for violence.

Research showed that the Oakland program was associated with a city-wide 32 percent reduction in shootings through 2017 that was concentrated in the areas and groups that were engaged by the program.61 Importantly, the partnership between communities, CVI programs, and law enforcement also facilitated important reforms in policing. A large reduction in shootings was achieved while reducing arrests and excessive use of force by police.62

State-level efforts to address community gun violence:

An increasing number of states have begun to build infrastructure to support CVI through sustained funding, technical assistance, and coordination. In 2017, only five states funded CVI related efforts; by 2021, fifteen states have funded such efforts committing to a total of $690 million.63

State-level efforts vary widely in the types of CVI programs they support and the ways they support such programs. Some states primarily fund CVI models, like group violence intervention, which rely on law enforcement-community partnerships, while, others support non-law enforcement interventions, like violence interruption and hospital-based intervention programs.

Evaluations of state level efforts in Connecticut and Massachusetts – early states to fund CVI have found promising results. Connecticut’s state-funded group violence intervention program was associated with a 21% decrease in shootings in New Haven each month that the program was in effect.64 Massachusetts’s state funded CVI program offers trauma informed case management and wrap-around services to young men who are involved in gun violence. Ongoing evaluations of this program, which now operates in 14 cities across the state, found that it was associated with lower rates of incarceration, reduced violent victimization among participants, and city level homicide and aggravated assault victimization rates among young men.65 In 2018, the program was associated with 815 fewer victims of violent crime among those ages 14-24. The evaluation found that for every $1 spent on the program, $5 in crime related costs were saved.66

Offices of Violence Gun Prevention

A growing number of states are investing in state level offices of gun violence prevention. These offices build the infrastructure to bring together various state agencies to more comprehensively address the multiple forms of gun violence. Many of these offices focus on CVI efforts, coordinating and funding CVI programs across the state. To date, at least six states have created offices of gun violence prevention.67

Federal efforts to address community gun violence:

Tireless advocacy from community violence intervention and prevention advocates across the country has led to sizable investments in community gun violence at the federal level and increasing capacity-building to support CVI programs. Through executive action, the Biden administration opened over 2 dozen grant programs spanning 5 departments to allow community violence intervention and prevention efforts to qualify for federal funding. As part of the Bipartisan Safer Communities Act, the U.S. Department of Justice received $150 million for CVI development, implementation and evaluation in the FY 2023 budget. 68 As a result of these new federal efforts, CVI organizations across the country have received unprecedented federal support.

In the Fall of 2023, the Biden Administration announced the creation of a White House Office of Gun Violence Prevention charged with helping to expand upon and implement the executive actions taken by the Biden Administratio, including providing ongoing support for CVI efforts.69

Taken together, these local, state and federal investments to build out strong community violence intervention and prevention programs are a promising development that has the potential to reduce community gun violence in communities across the United States.

Citations

- There is not a standardized definition of community gun violence. However, community gun violence, as defined on this page, accounts for the majority of gun homicides.

- Jacoby SF, Dong B, Beard JH, Wiebe DJ, & Morrison CN. (2018). The enduring impact of historical and structural racism on urban violence in Philadelphia. Social Science & Medicine.

- Sampson RJ. (2012). Great American city: Chicago and the enduring neighborhood effect. University of Chicago Press.

- Davis A, Kim R & Crifasi C. (2023). U.S. gun violence in 2021: An accounting of a public health crisis. Johns Hopkins Center for Gun Violence Solutions.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Health Statistics. About Underlying Cause of Death, 1999-2018.

- Aufrichtig A, Beckett L, Diehn J, & Lartey L. (2017). Want to fix gun violence in America? Go local. The Guardian.

- Acs G, Pendall R, Treskon M, & Khare A. (2017). The cost of segregation: National trends and the case of Chicago, 1990–2010. Urban Institute.

- Brocklin EV. (2016). Is America experienceing a murder outbreak? It depends on your block. The Trace.

- Team Trace. (2017). 15 census tracts, 97 fatal shootings and two different sides of American gun violence. The Trace.

- Davis A, Kim R, & Crifasi CK. (2023). A Year in Review: 2021 Gun Deaths in the U.S. Johns Hopkins Center for Gun Violence Solutions. Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health.

- Braga AA & Weisburd DL. (2015). Focused deterrence and the prevention of violent gun injuries: Practice, theoretical principles, and scientific evidence. Annual Review of Public Health.

- Braga AA. (2008). Problem-oriented policing and crime prevention. Criminal Justice Press.

- Decker SH. (1996). Collective and normative features of gang violence. Justice Quarterly.

- McLively M & Nieto B. (2019). A case study in hope: Lessons from Oakland’s remarkable reduction in gun violence. Giffords Law Center.

- Corsaro N & Engel RS. (2015). Most challenging of contexts: Assessing the impact of focused deterrence on serious violence in New Orleans. Criminology & Public Policy.

- Papachristos AV & Wildeman C. (2014). Network exposure and homicide victimization in an African American community. American Journal of Public Health.

- Jacoby SF, Dong B, Beard JH, Wiebe DJ, & Morrison CN. (2018). The enduring impact of historical and structural racism on urban violence in Philadelphia. Social Science & Medicine.

- Lane SD, Keefe RH, Rubinstein R, Levandowski BA, Webster N, Cibula DA, Boahene AK, Dele-Michael O, Carter D, Jones T, Wojtowycz M. (2008). Structural violence, urban retail food markets, and low birth weight. Health & place.

- Poverty to Prosperity Program and the CAP Economic Policy Team (2015). Expanding opportunities in America’s urban areas. Center for American Progress.

- Erickson D, Reid C, Nelson L, O'Shaughnessy A, & Berube A. (2008). The enduring challenge of concentrated poverty in america: Case studies from communities across the US. Federal Reserve System; Brookings Institution.

- Neighborhood poverty and household financial security. (2016). Pew Charitable Trusts.

- Morgan I & Amerikaner A. (2018). Funding Gaps 2018: An analysis of school funding equity across the U.S. and within each state. The Education Trust.

- Benzow A & Fikri K. (2020). The expanded geography of high-poverty neighborhoods. Economic Innovation Group.

- Bieler S, Kijakazi K, La Vigne N, Vinik N, & Overton S. (2016). Engaging communities in reducing gun violence. Urban Institute.

- Rowhani-Rahbar A, Quistberg DA, Morgan ER, Hajat A, & Rivara FP. (2019). Income inequality and firearm homicide in the US: a county-level cohort study. Injury Prevention.

- Kennedy BP, Kawachi I, Prothrow-Stith D, Lochner K, & Gupta V. (1998). Social capital, income inequality, and firearm violent crime. Social Science & Medicine.

- In the crossfire: The impact of gun violence on public housing communities (2000). US Department of Housing and Urban Development.

- Bieler S, Kijakazi K, La Vigne N, Vinik N, & Overton S. (2016). Engaging communities in reducing gun violence. Urban Institute.

- Bieler S, Kijakazi K, La Vigne N, Vinik N, & Overton S. (2016). Engaging communities in reducing gun violence. Urban Institute.

- Burnside AN, Gaylord-Harden NK. (2019). Hopelessness and delinquent behavior as predictors of community violence exposure in ethnic minority male adolescent offenders. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology.

- Desmond M, Papachristos AV, & Kirk DS. (2016). Police violence and citizen crime reporting in the black community. American Sociological review.

- Braga AA & Cook PJ. (2023). Policing Gun Violence: Strategic Reforms for Controlling Our Most Pressing Crime Problem.

- Braga, A. A., Turchan, B., Papachristos, A. V., & Hureau, D. M. (2019). Hot spots policing of small geographic areas effects on crime. Campbell systematic reviews.

- Braga AA, Weisburd D, Turchan B. (2019). Focused deterrence strategies effects on crime: A systematic review. Campbell Systematic Reviews.

- Lowery W, Kimbriell K, Mellnik T, &Rich S. (2018) Where Killings go Unsolved. The Washington Post.

- Ryley S, Campbell S, Singer-Vine J. (2019). Shoot someone in a major US city, and the odds are you’ll get away with it. Buzzfeed News, The Trace.

- Braga AA. (2021). Improving police clearance rates of shootings: A review of the evidence. Manhattan Institute.

- Tyler TR, Goff PA, & MacCoun RJ. (2015). The impact of psychological science on policing in the United States: Procedural justice, legitimacy, and effective law enforcement. Psychological science in the public interest.

- Tyler TR, Goff PA, & MacCoun RJ. (2015). The impact of psychological science on policing in the United States: Procedural justice, legitimacy, and effective law enforcement. Psychological science in the public interest.

- Balko R. (2020). There’s overwhelming evidence that the criminal justice system is racist. Here’s the proof.Washington Post.

- Leovy J. (2015). Ghettoside: A true story of murder in America. Spiegel & Grau.

- Desmond M, Papachristos AV, & Kirk DS. (2016). Police violence and citizen crime reporting in the black community. American sociological review.

- Hemenway D, Azrael D, & Miller M. (2017). Whose guns are stolen? The epidemiology of gun theft victims. Injury Epidemiology.

- Freskos B. (2017). Missing pieces: gun theft from legal owners is on the rise, quietly fueling violent crime across America. The Trace.

- Webster DW, Vernick JS, McGinty EE, & Alcorn, T. (2013). “Preventing the Diversion of Guns to Criminals Through Effective Firearm Sales Laws,” in Reducing Gun Violence in America: Informing Policy with Evidence and Analysis. The Johns Hopkins University Press

- Webster DW, Vernick JS, McGinty EE, & Alcorn, T. (2013). “Preventing the Diversion of Guns to Criminals Through Effective Firearm Sales Laws,” in Reducing Gun Violence in America: Informing Policy with Evidence and Analysis. The Johns Hopkins University Press.

- Crifasi CK, Merrill-Francis M, McCourt A, Vernick JS, Wintemute GJ, & Webster DW. (2018). Correction to: Association between firearm laws and homicide in urban counties. Journal of Urban Health.

- Inside the gun shop: Firearms dealers and their impact. (2023). Everytwown research & Policy.

- Giffords Law Center. (2023). Gun Industry Immunity.

- Telep CW, Weisburd D. (2016). Policing. What works in crime prevention and rehabilitation: Lessons from systematic reviews. Springer.

- Quattlebaum M, Meares TL, & Tyler T. (2018). Principles of procedurally just policing. The Justice Collaboratory at Yale Law School.

- President’s Task Force on 21st Century Policing. (2015). Final Report of the President’s Task Force on 21st Century Policing. Washington, DC: Office of Community Oriented Policing Services.

- Webster, D. W., Tilchin, C. G., & Doucette, M. L. (2023). Estimating the Effects of Safe Streets Baltimore on Gun Violence 2007-2022. Johns Hopkins University.

- Butts JA, Wolff KT, Misshula E, & Delgado S. (2015). Effectiveness of the Cure Violence Model in New York City. John Jay College of Criminal Justice, Research & Evaluation Center.

- Braga AA, Weisburd D, & Turchan B. (2018). Focused deterrence strategies and crime control: An updated systematic review and meta‐analysis of the empirical evidence. Criminology & Public Policy.

- Abt TP (2017). Towards a framework for preventing community violence among youth. Psychology, Health & Medicine.

- Heller SB, Shah AK, Guryan J, Ludwig J, Mullainathan S, & Pollack HA. (2017). Thinking, fast and slow? Some field experiments to reduce crime and dropout in Chicago. The Quarterly Journal of Economics.

- Azrael D, Braga AA, O'Brien M. (2012). Developing the capacity to understand and prevent homicide: An evaluation of the Milwaukee Homicide Review Commission. U.S. Department of Justice.

- Azrael D, Braga AA, O'Brien M. (2012). Developing the Capacity to understand and prevent homicide: An evaluation of the Milwaukee Homicide Review Commission. U.S. Department of Justice.

- Branas CC, Kondo MC, Murphy SM, South EC, Polsky D, & MacDonald JM. (2016). Urban blight remediation as a cost-beneficial solution to firearm violence. American Journal of Public Health.

- Braga AA, Bareao L, Zimmermand G, ... & Farrell, C. (2019). Oakland Ceasefire Evaluation. Report to the City of Oakland. May 2019. https://cao-94612.s3.amazonaws.com/documents/Oakland-Ceasefire-Evaluation-Final-Report-May-2019.pdf

- Giffords Law Center to Prevent Gun Violence, Faith in Action, and Black and Brown Gun Violence Prevention Consortium. A Case Study in Hope: Lessons from Oakland’s Remarkable Reduction in Gun Violence. April 2019. https://policingequity.org/images/pdfs-doc/reports/A-Case-Study-in-Hope.pdf

- McKlively M. (2021). State support for CVI: Trends and best practices. Presentation referenced in: Kutcsch T. (2021). Pledges keep rolling in for state-funded community violence intervention. The Trace

- Sierra-Arevalo M, Charette Y, & Papachristos AV. (2016). Evaluating the Effect of Project Longevity on Group-Involved Shootings and Homicides in New Haven. Crime & Delinquency. Note: Researchers found that a 2.38 decrease in shootings (fatal and non-fatal) from 11.64 to 9.26 per month can be attributed to the enactment of the program. Thus, the program was linked to a 21% decrease in shootings per month.

- National Insitute of Justice. Program profile: Safe and successful youth initiative (SSYI Massachusetts). Crime Solutions. Available: https://crimesolutions.ojp.gov/ratedprograms/717#7-0

- Campie T, Read N. (2020). The Massachusetts safe and successful youth initiative: A promising statewide approach to youth gun and gang violence prevention. Translational Criminology.

- States with offices of gun violence prevention: California, Colorado, Illinois, New York, North Carolina, Washington.

- Frequently asked questions about community-based violence intervention programs. (2022). The Center for American Progress.

- The Office of Gun Violence Prevention. The White House. Available: https://www.whitehouse.gov/ogvp/